The North American Monsoon is responsible for pumping subtropical moisture into the southwestern United States every summer, moisture which ultimately supplies the fuel for Colorado’s daily summertime thunderstorms — rain we desperately need in the Front Range right now following months scarce precipitation and worsening drought. However, the arrival and intensity of the summer monsoon varies substantially from year to year, especially in our area. In this long-range outlook, we discuss the developing dire drought situation, the current state of the monsoon, what’s happening with El Niño, and what to expect for weather in the coming months across Front Range Colorado.

Key Highlights from This Post:

- Following more than two months of dry weather, drought has recently returned to the Front Range and fire danger is growing

- Monsoon conditions have officially commenced across the Desert Southwest with a surplus of moisture already flowing into the Four Corners region at times

- El Niño has dissipated, but La Niña is forming and should arrive later this summer

- During La Niña, the monsoon is usually suppressed southward leading to hotter and drier than normal conditions across the Front Range

- This hot/dry summer outcome for Colorado is also predicted by climate experts, as well as favored by historical analogs and climate model forecasts

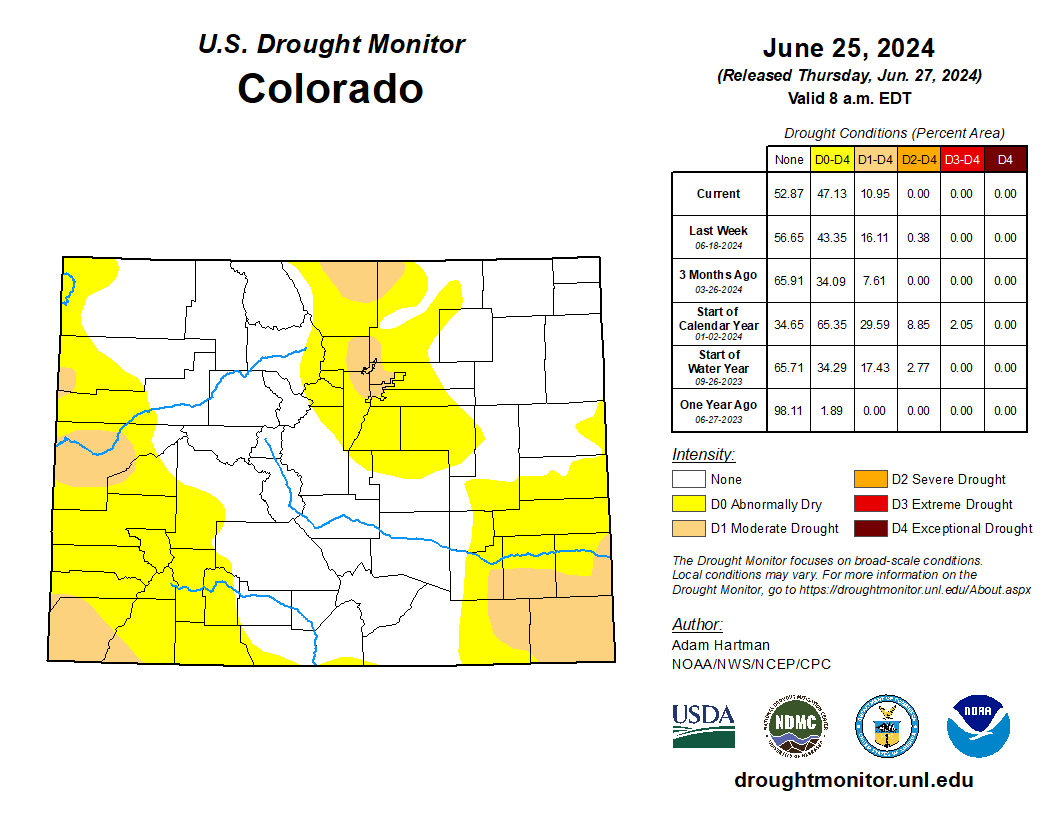

- Given the forecast, drought is expected to intensify further across the area in the coming months with a tough fire season ahead

Daily Forecast Updates

Get our daily forecast discussion every morning delivered to your inbox.

All Our Model Data

Access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather model graphics. Seriously — every one!

Ski & Hiking Forecasts

6-day forecasts for all the Colorado ski resorts, plus more than 120 hiking trails, including every 14er.

Smoke Forecasts

Wildfire smoke concentration predictions up to 72 hours into the future.

Exclusive Content

Weekend outlooks every Thursday, bonus storm updates, historical data and much more!

No Advertisements

Enjoy ad-free viewing on the entire site.

Drought has returned to the Front Range as fire danger grows

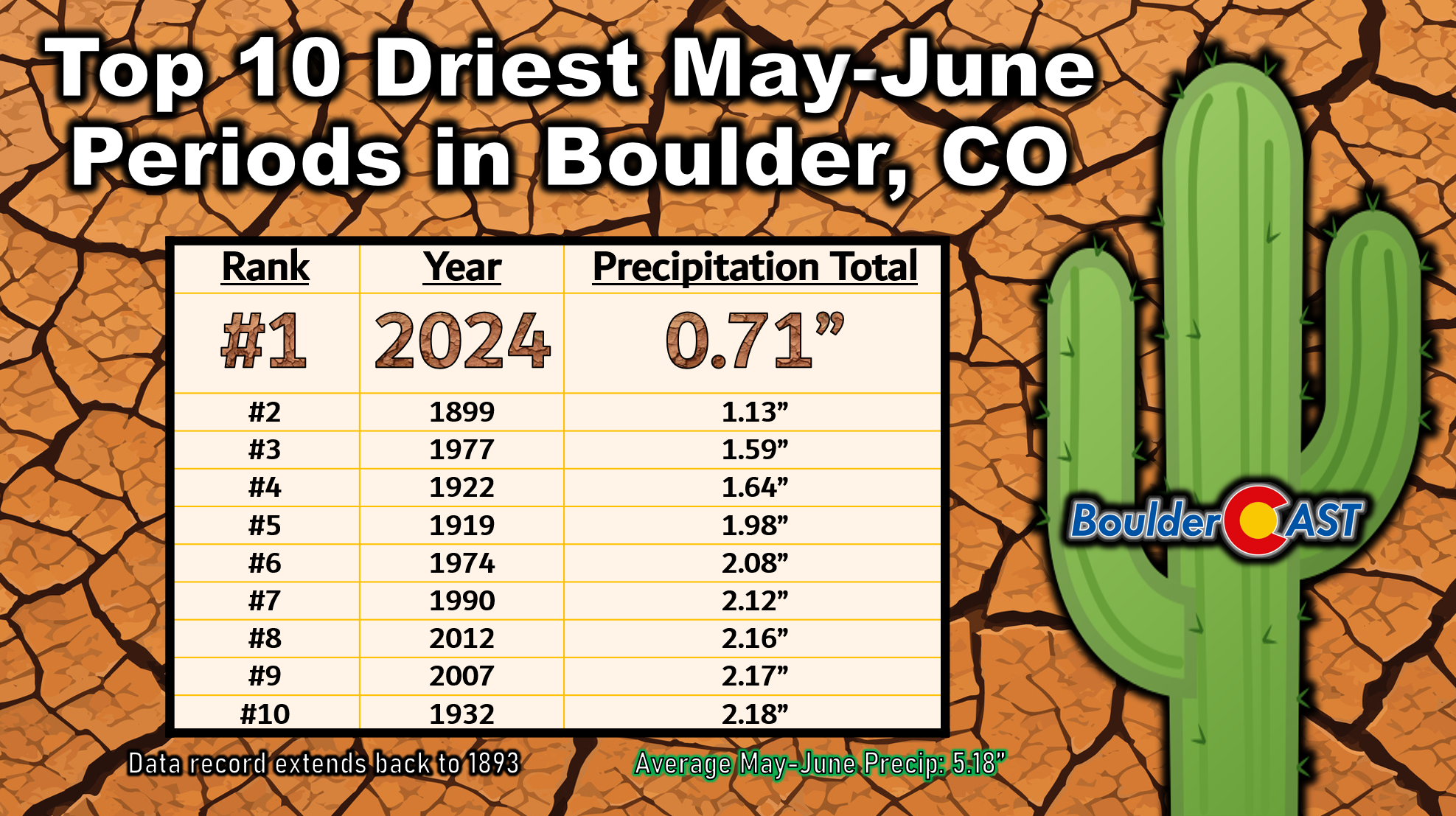

If you’ve been following along with us or our weather the last two months (or have even the most average of observational skills), you’ll know that local conditions have grown more dire with May landing as one of the all-time driest in many Front Range cities and now June unfolding even drier than that in some areas. Boulder in particular has been one of the hardest hit (or not hit?), officially receiving just 0.71″ of rainfall in the months of May and June combined — an all-time low since record-keeping began in the 1890s!

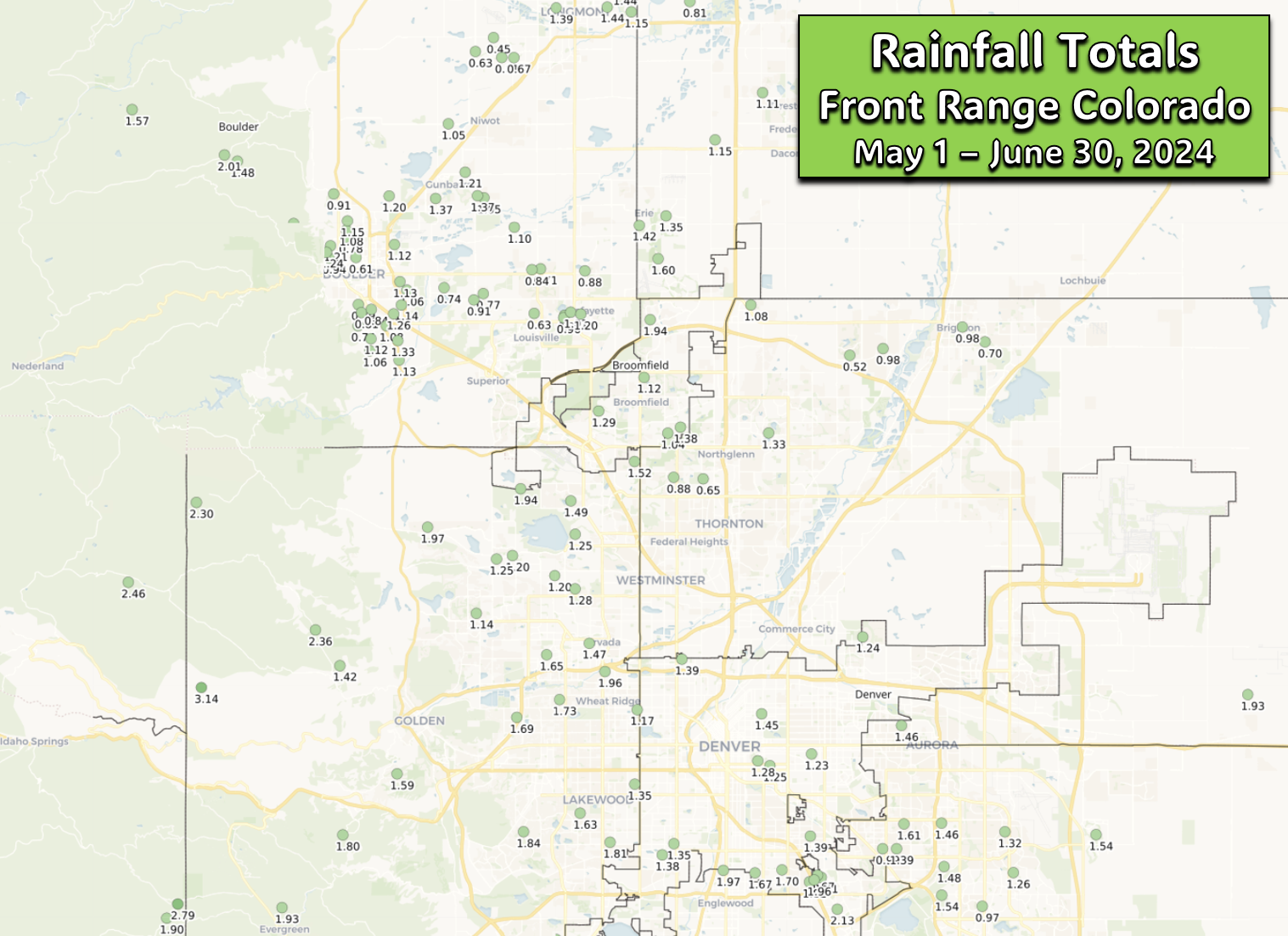

Oddly enough it actually rained 32 out of the 61 days in that period in Boulder, but most of time it was just a sprinkle resulting in a trace of rain or a few hundredths at best. That is the nature of our warm season rains though — they are always hit or miss. However, Boulder isn’t that much of an outlier. The entire Denver Metro area received way below normal rainfall in May and June, generally between 0.5 and 2″ across the region. Average during this period would be 3-4″ to the north/east and 4-6″ in the west/south.

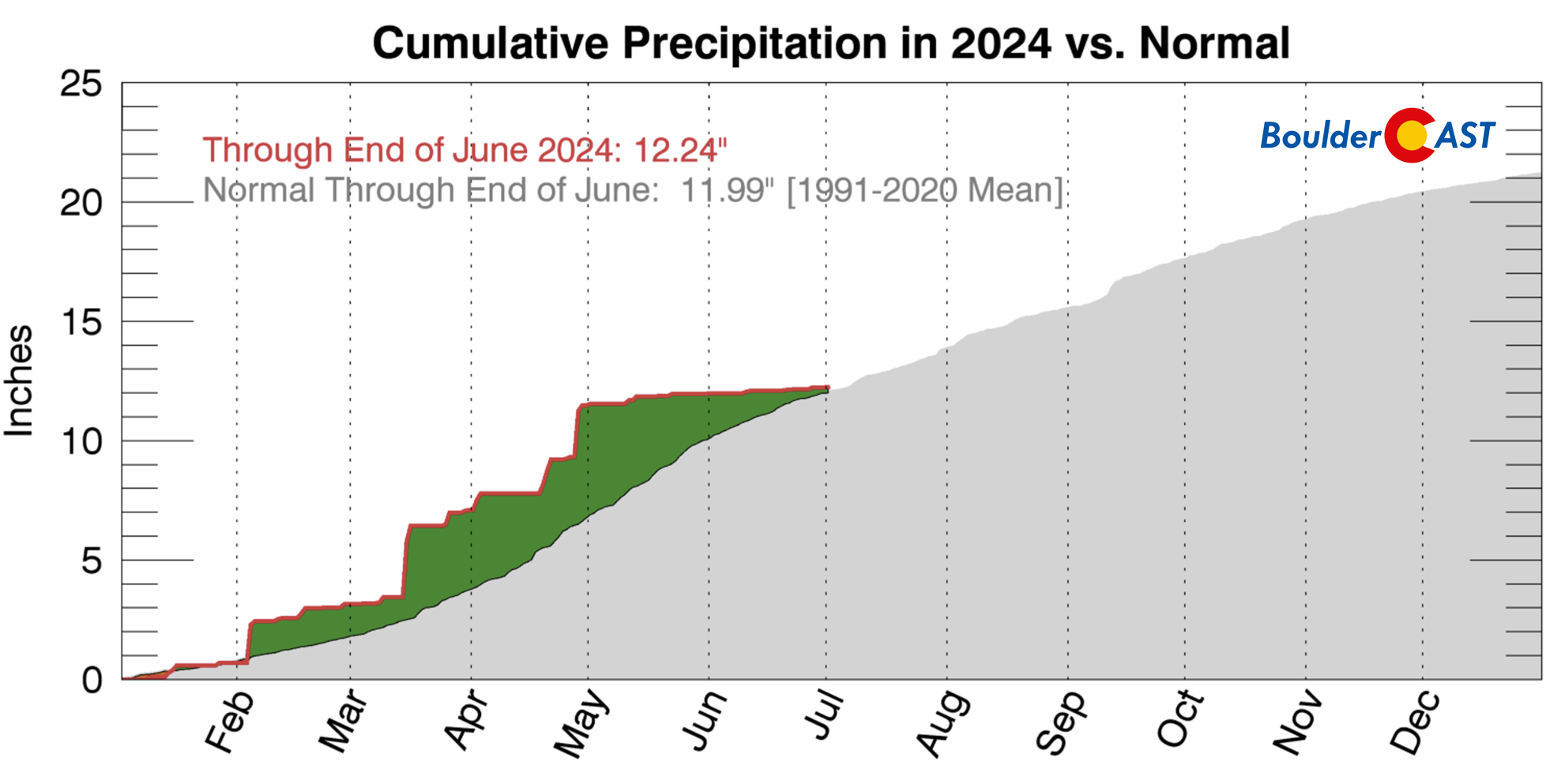

The craziest part is that the first chunk of the year was one of the all-time wettest for many of us. At one point, Boulder had a ~5.5″ precipitation surplus for 2024, thanks in large part to several massive dumps of rain and snow in the springtime. Who could forget the 22″ dumping of snow in mid-March or the super-soaker (mostly) rain storm we had in late April?

Despite a very wet start to 2024, drought has made an unfortunate return to the Front Range in June following weeks of scarce rainfall and toasty temperatures. Much of the Metro area, including Longmont, Broomfield, Boulder and Denver, are now experiencing Moderate Drought.

It is perhaps perfect timing that, here in early July, we’re about to run right into the normal start time for the summer monsoon! This glorious time of year sees our historical chances for measurable rainfall soar to over 40% daily by the end of July, up from only ~20% a few weeks earlier.

Unfortunately, the outlook for the summer ahead is far from a promising one. The rest of this rather lengthy post delves into how things may turn out the rest of summer for Front Range Colorado — and it is not looking good.

Monsoon Season Update

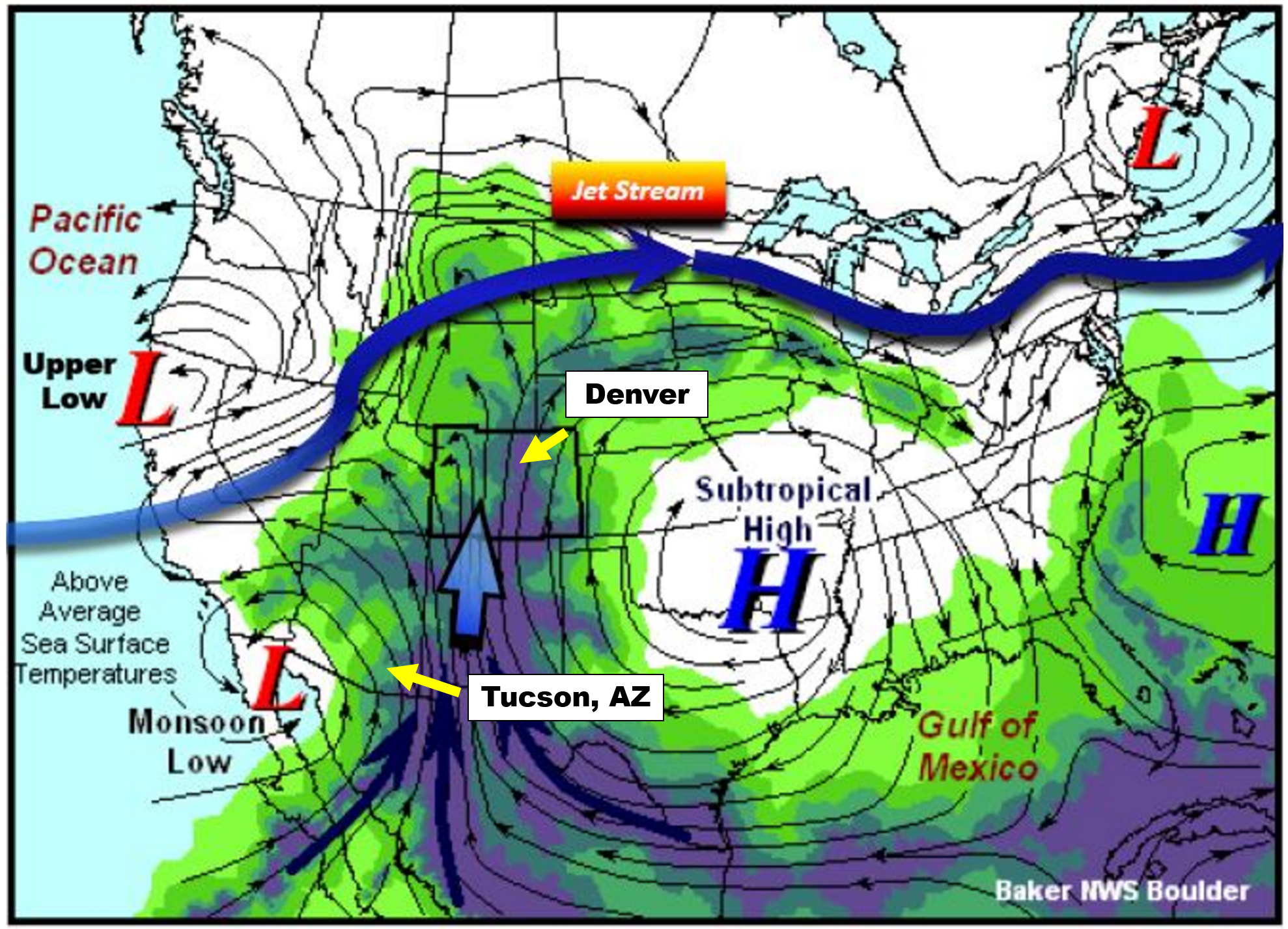

The diagram below shows the typical set-up for the North American Monsoon, the seasonal wind shift that brings soaking rains to Colorado and much of the Four Corners region each summer. A “monsoon” low pressure in southern California often teams up with high pressure in the southeastern United States to funnel relatively large quantities of low and mid-level moisture northward into the Desert Southwest. This moisture, which originates from both the Gulf of Mexico and the Gulf of California, is key to forming the widespread monsoon thunderstorms that are a staple of Colorado’s summer. The storms feed off of daytime solar heating — with the clouds and thunderheads forming over the terrain first due to the sloped mountain surfaces heating up quicker. As the storm clouds grow in the High Country, the prevailing winds from the west or southwest push the storms eastward across the Denver Metro area where outflows can help form subsequent new thunderstorms in a moisture-rich environment. Each evening, all of the storm activity generally dies out shortly after sunset. This diurnal cycle rinses and repeats all summer long, with the ever-changing influx of monsoon moisture content determining the exact location and coverage of the storms on any given day.

Monsoon set-up diagram | NWS Boulder

Officially, America’s Southwest Monsoon Season arbitrarily runs annually from June 15th to September 30th. So yes, monsoon season has technically already begun more than two weeks ago. However, the official season is not based on actual meteorological conditions, which can lead to some confusion. Think about it — just because the Atlantic Hurricane Season begins on June 1st doesn’t mean every rainstorm in Miami thereafter is a hurricane. Similarly, just because we’re in the midst of monsoon season already, doesn’t mean every time it rains in Denver that monsoon conditions are responsible or even occurring.

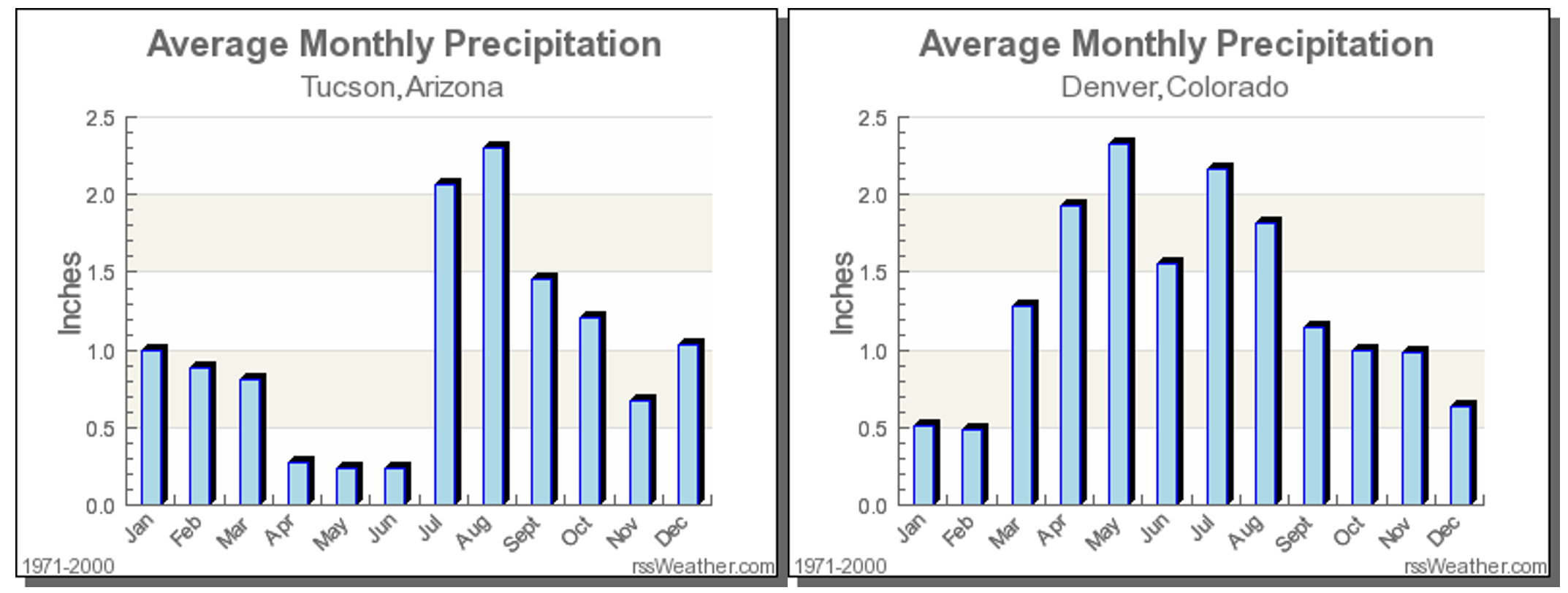

One way that we can track the true arrival of the North American Monsoon is to monitor the moisture content in the air over Arizona. Cities like Tucson (see location above) are much closer to the source of the moisture than we are here in Denver. The moisture more-or-less has to pass through Tucson as it moves northward into the United States. Tucson is also a pivot-point for the moisture plume itself. Think of Tucson as the “faucet”, with a “hose” of moisture wandering northward. Sometimes the hose if over Nevada, other times it meanders over Utah, and Colorado as well. While our monsoon here in Denver and Boulder is sporadic throughout July and August, owing to a fickle moisture hose, the hose’s faucet is nearly continuous for Tucson. For this reason, Tucson actually sees more monsoon rainfall than Denver on average, and has a notably more predictable and consistent monsoon climatology. For example, July’s average rainfall in Tucson exceeds the total for March, April, May and June COMBINED (below plot on the left). The monsoon is a much bigger reprieve for them than it is for us, especially considering the edge it can take off of those 110°F afternoons that frequently occur in the Sonoran Desert.

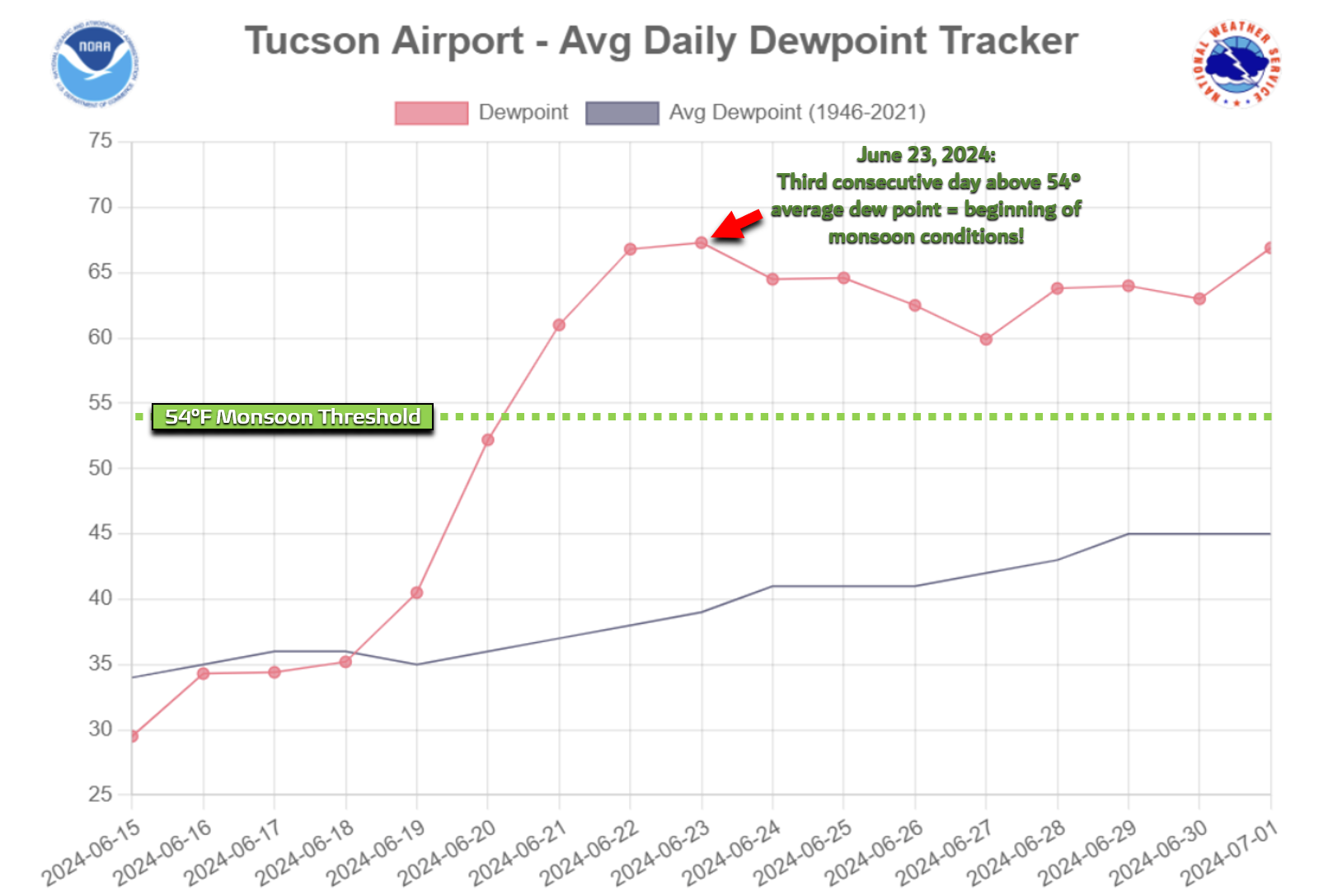

The graph below shows the daily average dew point values at Tucson Airport so far this summer. Once a dew point value of 54 degrees or higher is reached for three consecutive days, monsoon conditions are said to be occurring. The red line is the actual data from 2024. The gray line is climatology and the green line is the coveted 54-degree threshold for the monsoon.

As you can see from the graph, the last week or two has had well above normal moisture flowing into Tucson at the surface. The true onset of monsoon conditions was back June 23, the third consecutive day with values above 54°F. This is about 2 to 3 weeks earlier than the climatological normal! This early arrival doesn’t necessarily mean much since monsoon conditions often pulsate and end of monsoon conditions can fluctuate as well, but typically that occurs in mid-September for Tucson, and about two to three weeks earlier in Front Range Colorado. Along with the increased chance of daily thunderstorms, the monsoon brings more dangerous alpine hiking conditions, frequent evening rainbows, warmer nights, more lightning strikes to spark fires, and “stickier” air overall. As with anything weather-related, there are pros and cons to our summer monsoon!

Given that our area is currently morphing into a literal tinder box, we could certainly use any and all moisture that the commencing summer monsoon has to offer. Unfortunately, the outlook isn’t that great. Let’s discuss why.

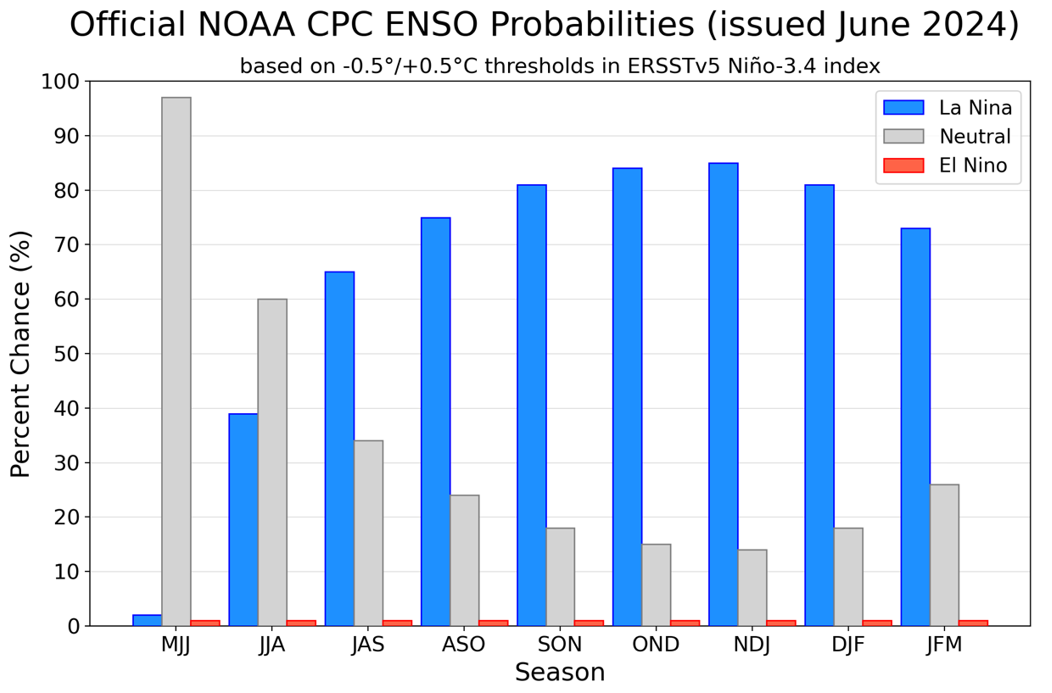

La Niña will soon rise from the ashes of El Niño

As of earlier this week, the abnormally strong El Niño we endured this past winter has finally met its demise. Sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean have been cooling since January, but it’s been slow-going. The warm sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific Ocean have remained persistent throughout the Spring but have now finally come down. Notice in the plots below how the warm anomalies have largely stayed the course in the various regions of the Equatorial Pacific. Niño 3.4 is the region most often used for determining the status of El Niño, which is defined as a value of +0.5°C or higher. In this case, we see that Niño Region 3.4 still remains positive into mid-June but is now under the 0.5°C threshold which signifies that ENSO-Neutral conditions are occurring. Don’t forget: ENSO = El Niño Southern Oscillation.

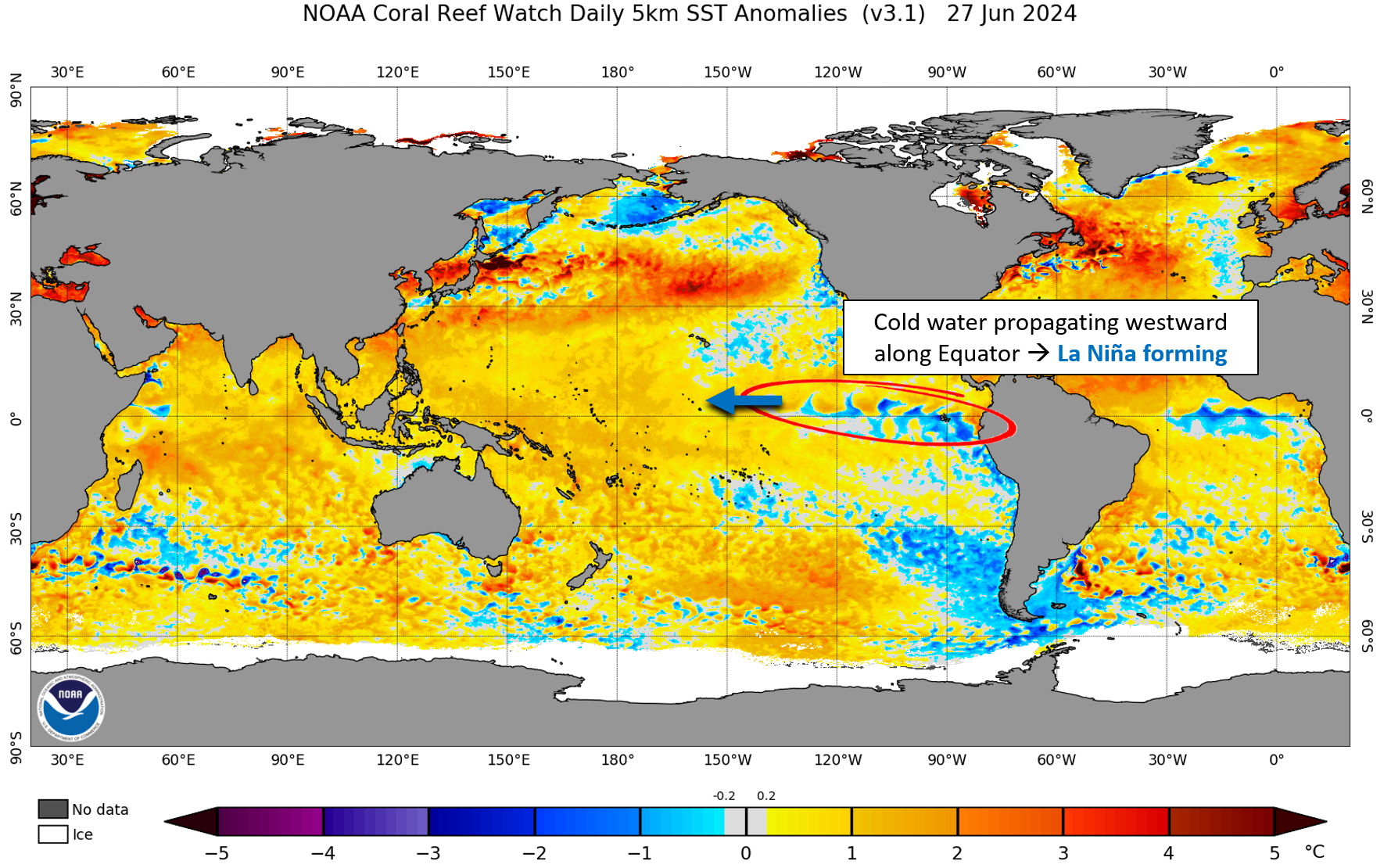

Current sea surface temperatures show the westward propagation of cold water anomalies across the Equatorial Pacific — yes, we are witnessing the birth of La Niña!

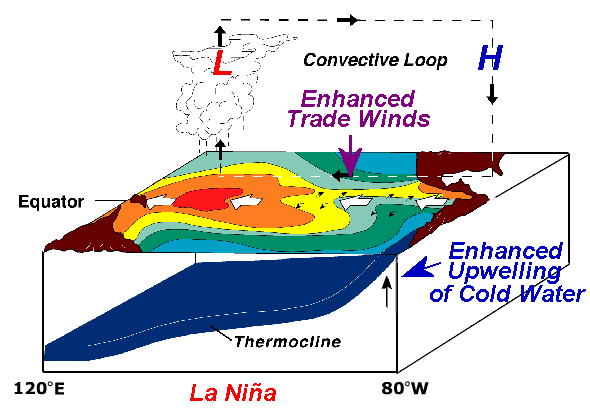

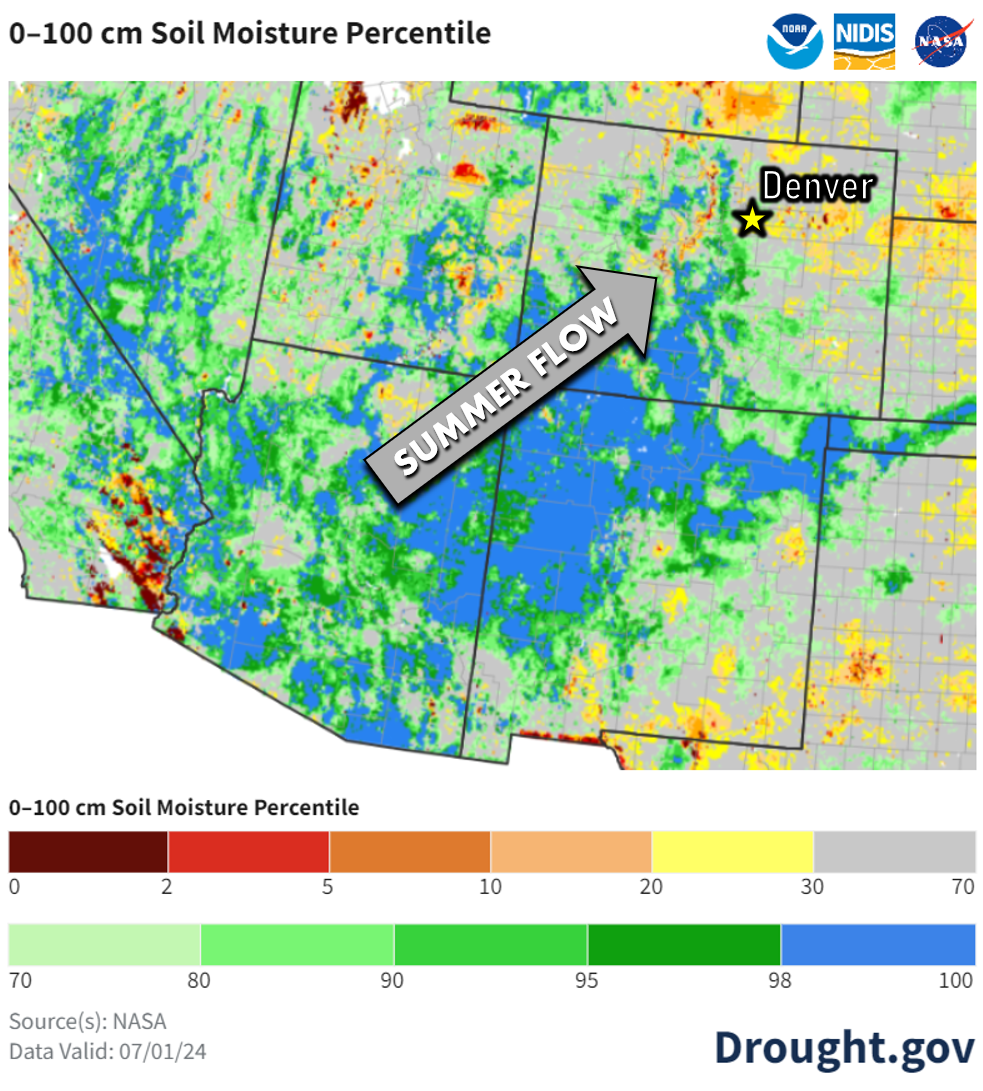

Let’s take a step back for a moment. Remember that La Niña is associated with cooler than normal sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, with enhanced easterly trade winds along the Equator and a shift of the warmest waters westward in the Pacific towards Polynesia, as shown in the 3D diagram below. Large-scale upward motion in the atmosphere and the resulting thunderstorm development along the Equator follow the warm pool in ocean water westward. This creates a convective loop across the expansive Pacific Ocean from west to east (shown above). These are just the localized effects of La Niña. Our atmosphere and ocean are intimately coupled on a global scale. This altered circulation on the scale of the massive Pacific Ocean leads to locations all around the world, including Colorado, being influenced by ENSO in one way or another.

The ongoing transition to La Niña won’t happen immediately. The Pacific Ocean is huge and water currents are much slower than the winds in the atmosphere. The latest ENSO forecast calls for La Niña to take over sometime between early August and early September, with a weak to moderate intensity La Niña then likely to persist through the upcoming Fall and Winter.

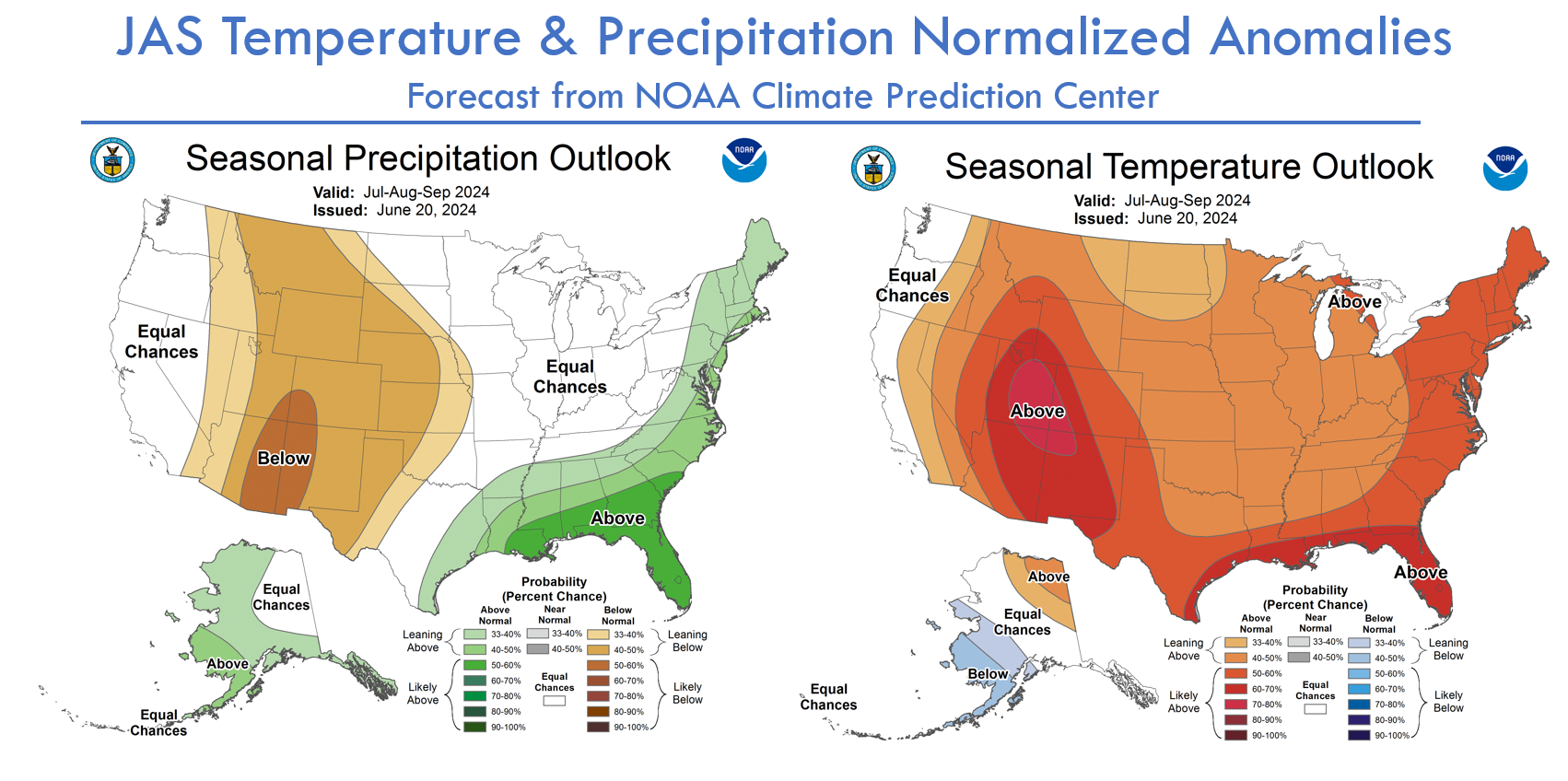

Nonetheless, La Niña developing during the back half of summer is generally bad news for the Front Range and most of Colorado. This is because the summer monsoon pattern is often suppressed further south during La Niña, whereas El Niño amplifies the reach of the monsoon into Colorado. Let’s walk through some data to confirm this.

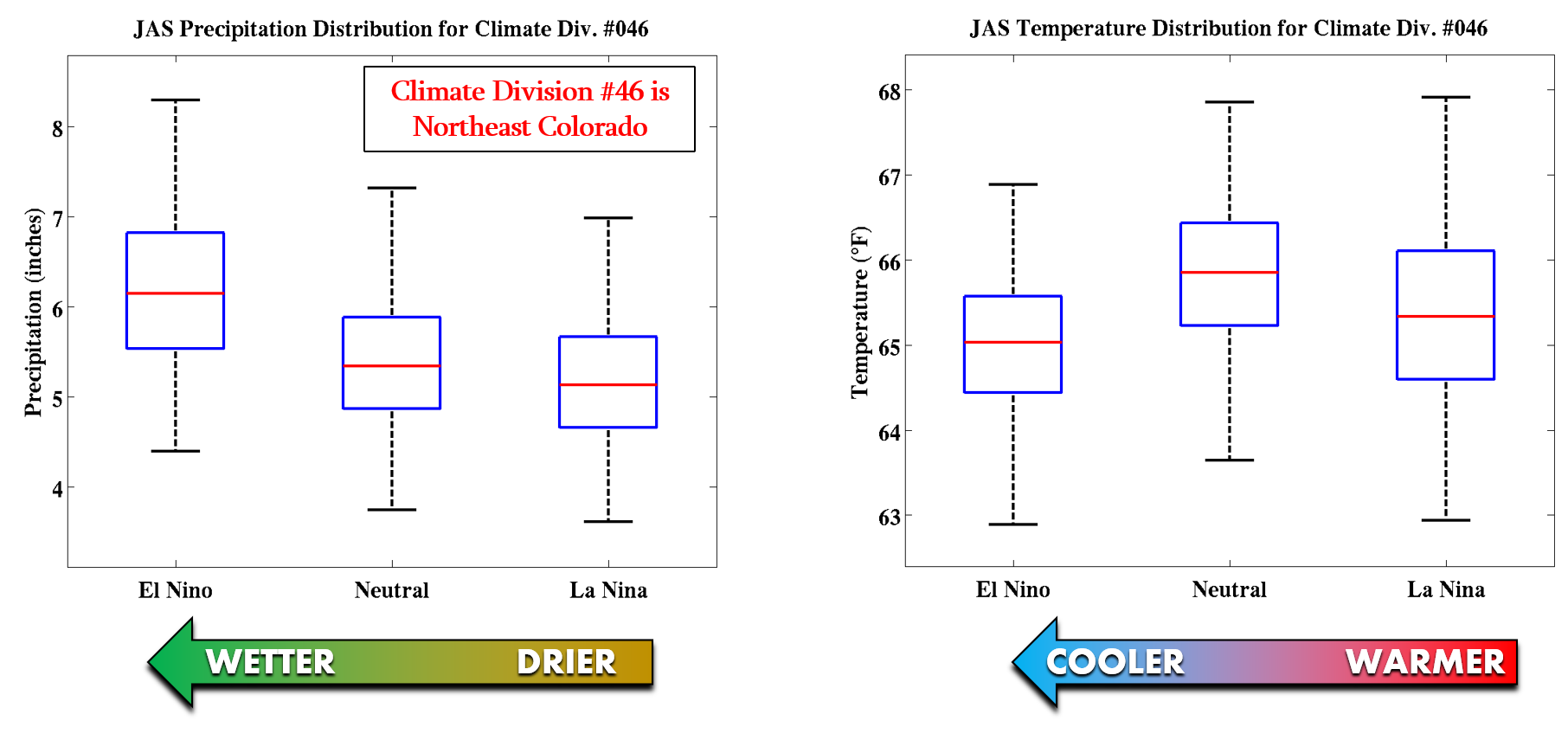

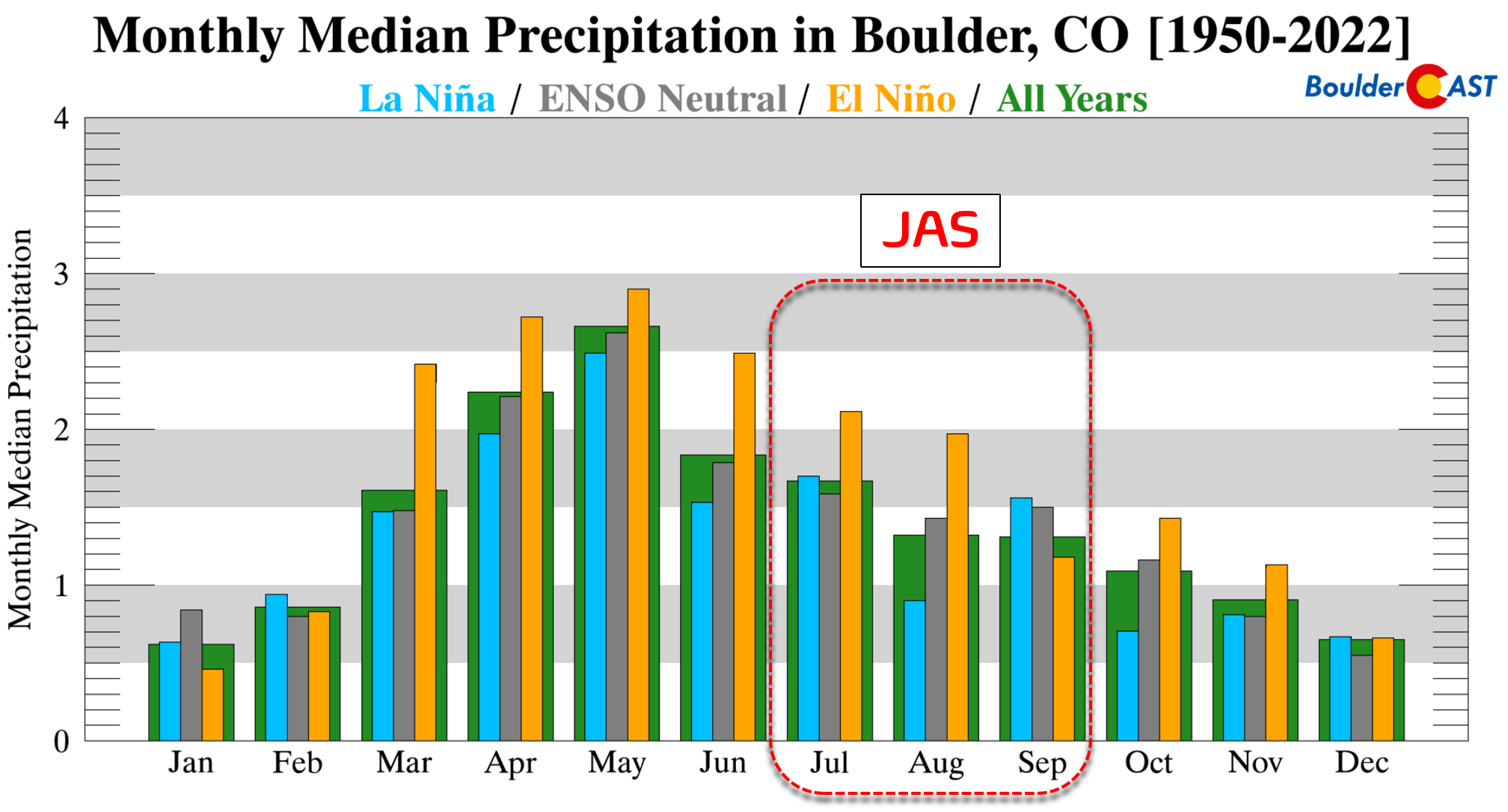

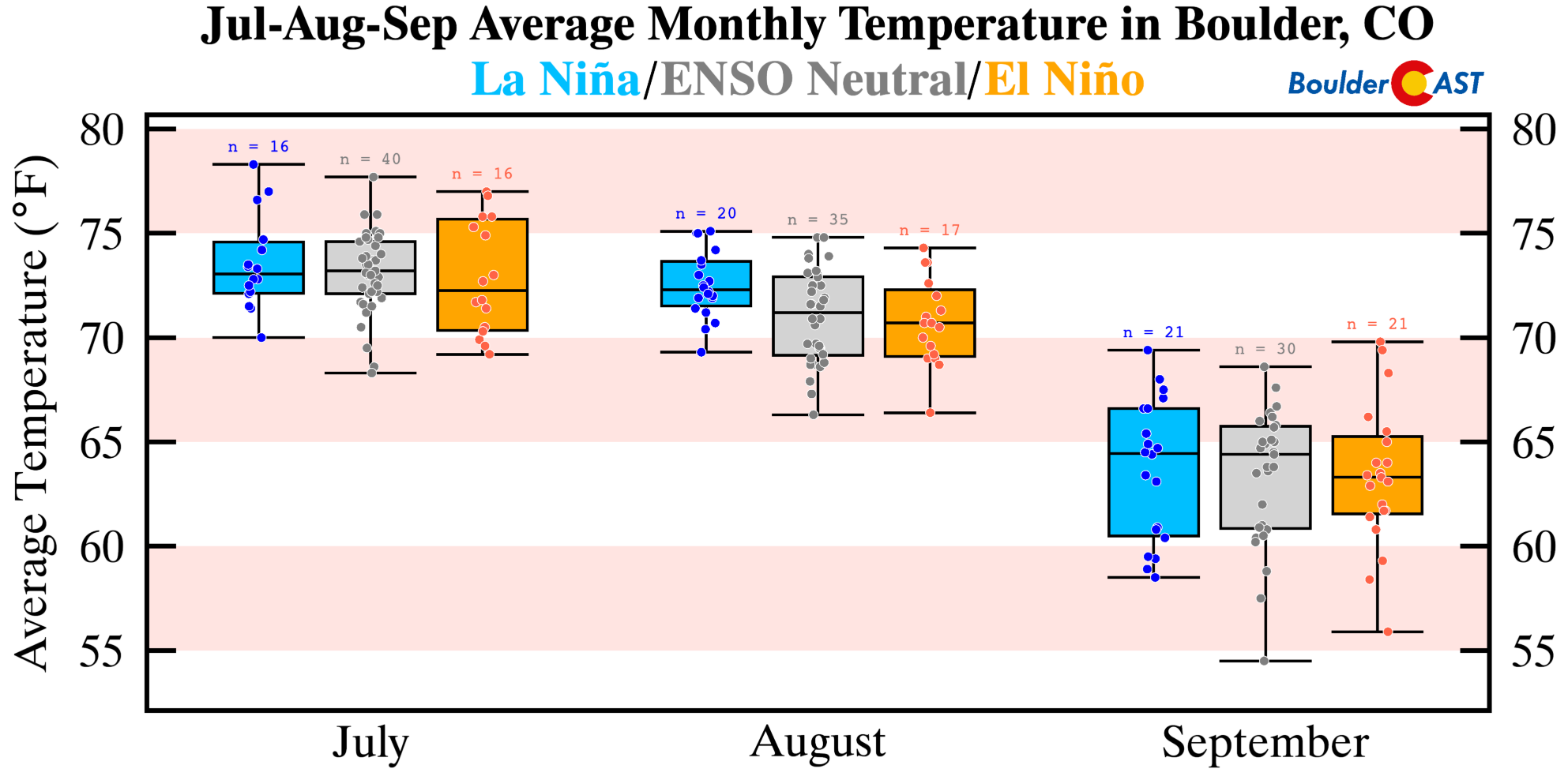

How ENSO impacts summers in Colorado

Shown below are box-and-whisker plots of precipitation (left) and temperature (right) for Climate Division #46 during the various phases of ENSO for the months of July, August and September (JAS). This is essentially the region comprising northeast Colorado and also some of north-central Colorado. A clear trend is evident from wetter and cooler conditions during El Niño towards warmer and drier conditions during La Niña, with ENSO-Neutral conditions landing somewhere in the middle. The sooner La Niña develops this summer, the worse off we’ll be for monsoon rainfall here in northern Colorado.

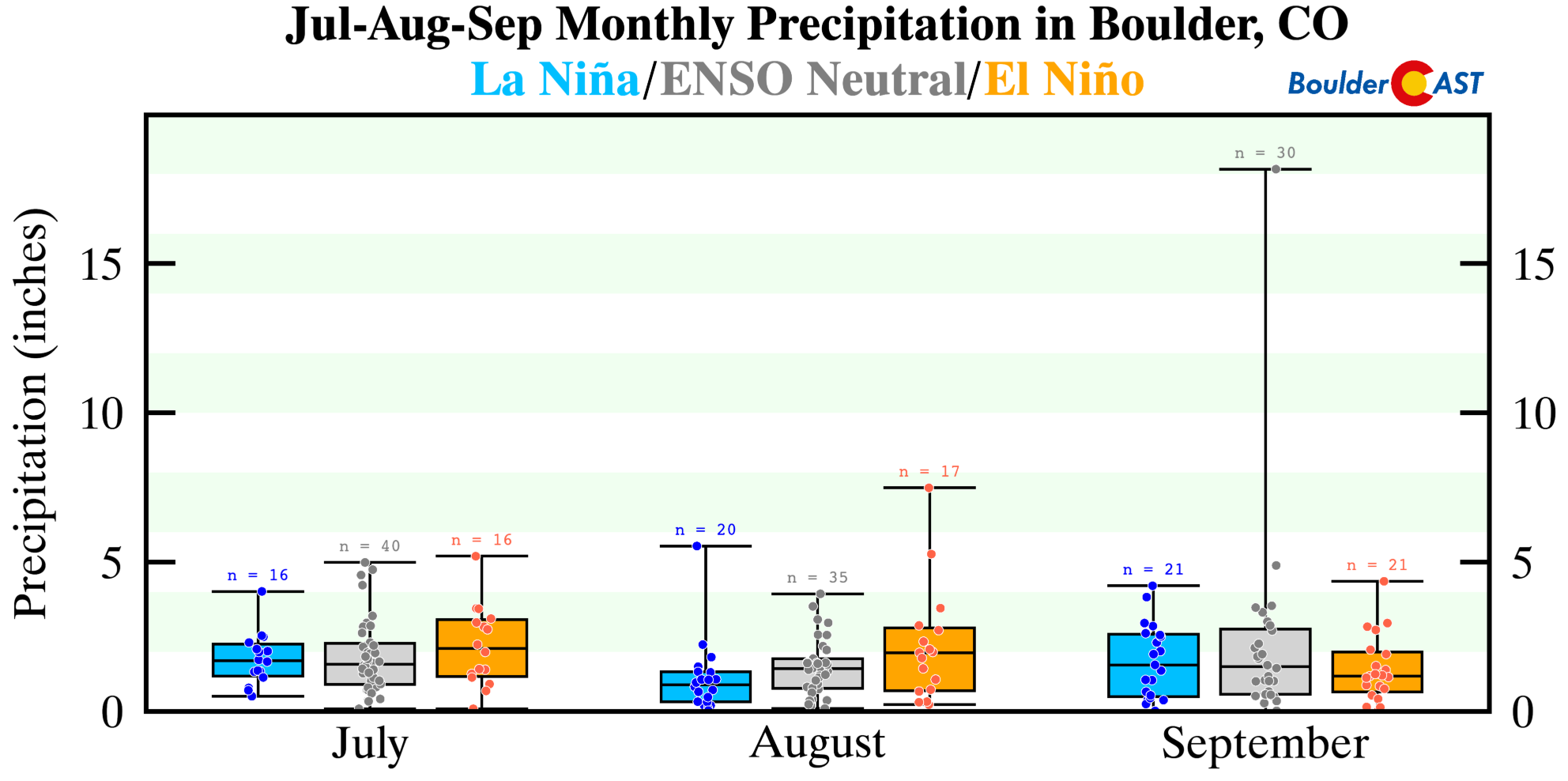

If we look at the historical data just for Boulder, we see the same trend in summer-time precipitation. July and August (peak monsoon months) are notably drier during La Niña compared to El Niño, though that trend reverses in September. Apologies….this precipitation graphic is a bit harder to read due to a single extreme data point. Yes, we’re referencing the 18 inches of rain that fell in Boulder during the 2013 Flood (which was an ENSO-Neutral September)!

Total precipitation amounts in JAS decline nearly 30% during La Niña compared to El Niño. Here are the median precipitation amounts for JAS in Boulder:

- La Niña: 4.1″

- ENSO-Neutral: 4.5″

- El Niño: 5.7″

Switching gears over to temperatures, we note the same trend in Boulder that we saw earlier for all of northeast Colorado. Less frequent monsoon clouds and thundershowers during La Niña allows for more scorching summer days across the High Plains of eastern Colorado. La Niña summers are notably warmer by 2 to 3°F overall in Boulder, with ENSO-Neutral conditions not much different than La Niña.

Summer 2024 Outlook

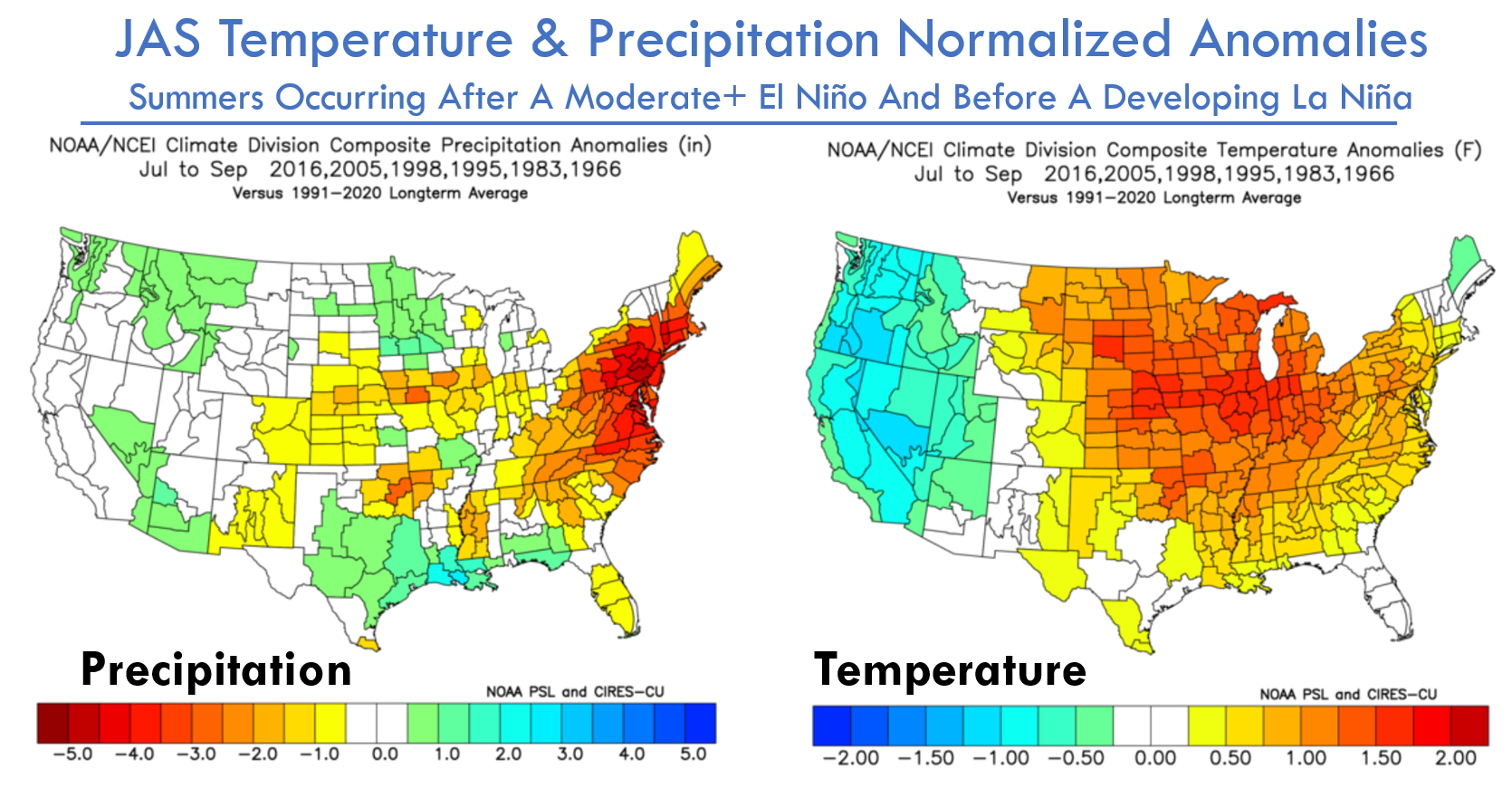

So far, looking at data generally pertaining to ENSO patterns, we would expect a drier and warmer than normal next three months (July through September). We can’t stop there though. Let’s take a quick check of the historical analog patterns relevant to the current situation. Shown below are JAS anomalies of precipitation (left) and temperature (right) for historical ENSO-Neutral summers that were sandwiched between a dissipating moderate or stronger El Niño and a developing La Niña. This situation has occurred roughly six times in the last half century or so. Note that conditions across eastern Colorado under this setup generally trend slightly warmer and slightly drier than normal — that is, towards a less active monsoon season.

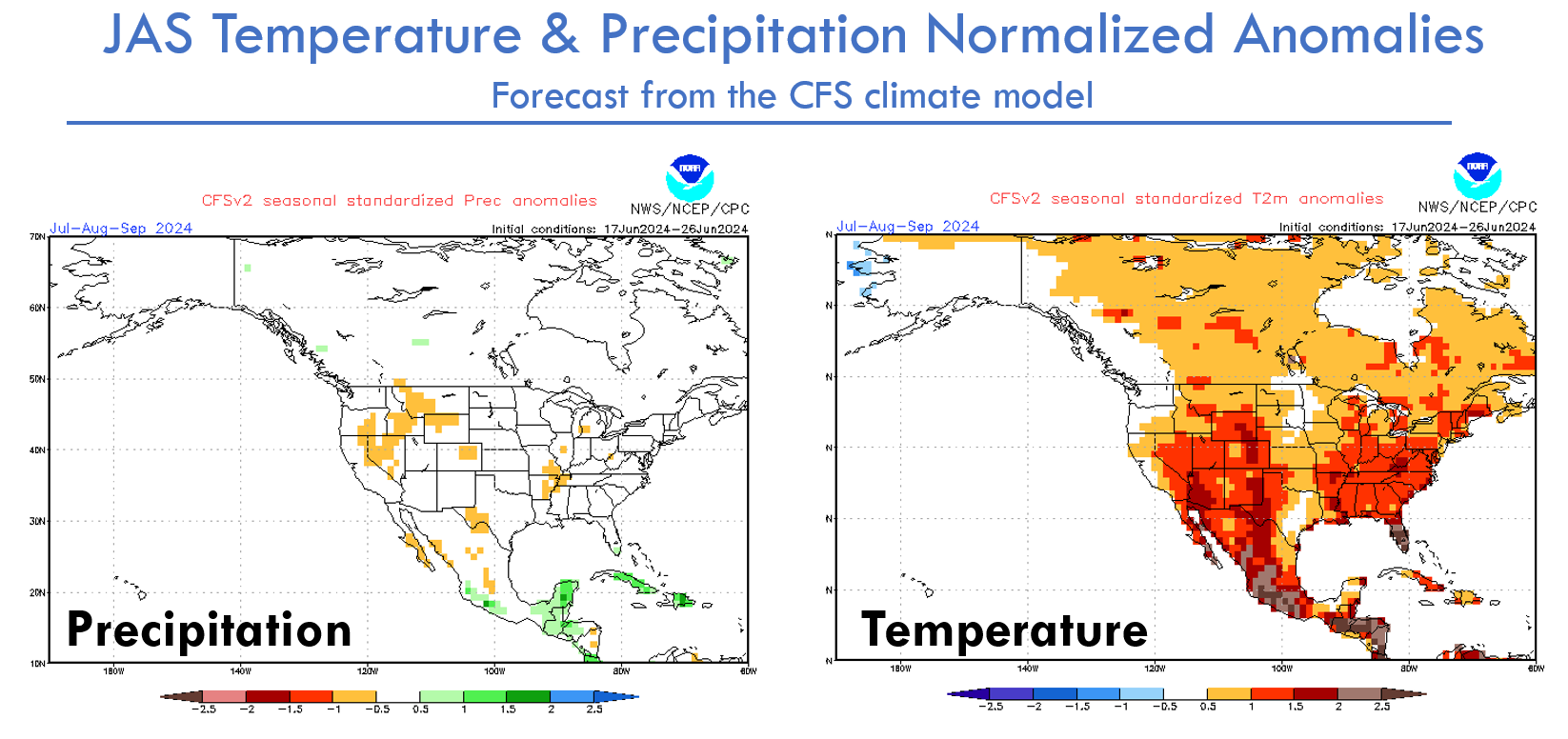

So far we have reviewed the outcomes from past summer seasons, and nothing more. Let’s now take a look at actual future forecasts. First, the prediction from a popular climate model, the CFS. This model is predicting a warm summer for most of North America (below right). For precipitation (below left), the CFS model is predicting basically near-average precipitation for much of the country. There are just a few hints of dry weather across the West, including here in the Front Range.

Below is the latest JAS forecast from the Climate Prediction Center (CPC). They are expecting elevated chances of a dry summer across much of the West, including you guessed it, the Front Range. They also predict increased chances for warmer than normal temperatures for nearly the entire United States. The strongest warm signals they say will be over the Four Corners region, with the Denver Metro area on the edge of this bullseye.

Overall we have found that past ENSO trends, historical analogs, current model forecasts and expert projections from climatologists all point towards a dry and hot summer of 2024 here in the Front Range. But remember, as with most of weather, nothing is ever set in stone. ENSO is a distant weather pattern that just gives us hints about conditions that are slightly more likely to occur in the months ahead. Furthermore, there are also at least two other key factors for our summertime weather we must also consider…

1) Eastern Pacific Tropical Cyclone Activity

Hurricane season across the eastern Pacific Ocean will ramp up as summer wears on. Much more-so than the Atlantic, Pacific hurricanes can and do influence the weather in Colorado through deep tropical moisture injections when they curve northeastward into Baja California. Recent examples of this happening include Hurricane Rosa and Hurricane Bud in 2018, and Hurricane Hilary in 2023. The bad news on this front is that the imminent transition to La Niña will likely reduce the number of tropical cyclones forming in the Eastern Pacific Ocean due to the cooler waters in their source region. Thus, we can’t really count on remnant hurricanes to help sow rainfall in our area this summer.

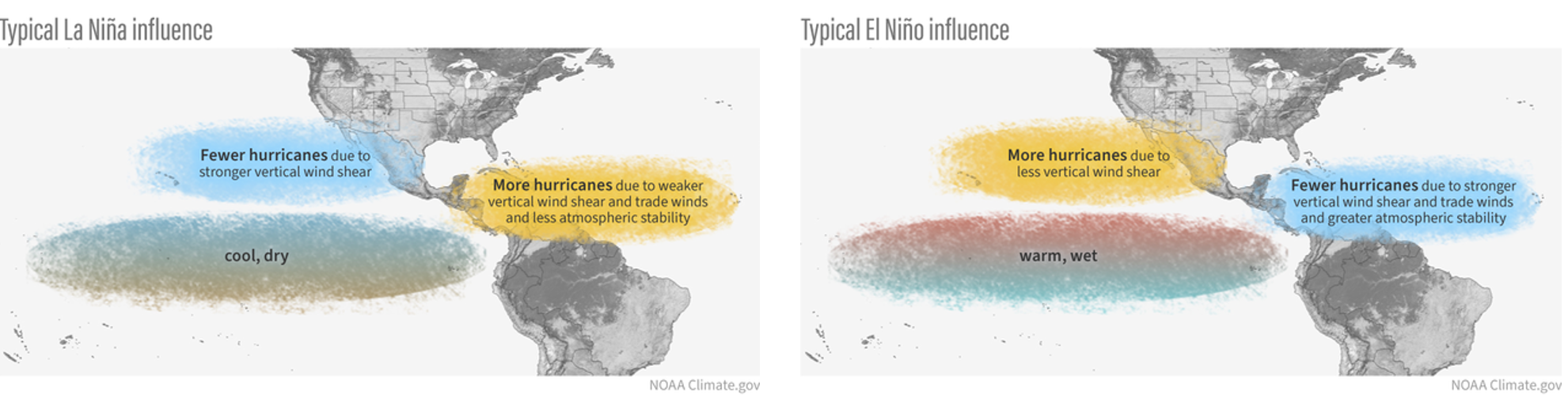

2) Upstream Soil Moisture

The water content of the soil upstream can also play a role in thunderstorm development here in Colorado. After all, moisture is moisture and the rain clouds don’t really care where it came from! Damp and soggy soils over a large area will evaporate in time and can supply moisture for rainfall to develop downstream. The broad atmospheric flow in the summer generally comes from the southwest to reach Denver so that is our “upstream”. As it stands now in early July, a large portion of Arizona, New Mexico, southwest Colorado and Utah have above normal soil moisture. While not as important as monsoon moisture transport coming from huge bodies of water, this soil moisture does play a smaller role. Even better, it’s a positive feedback loop — more rain leads to higher soil moisture, and higher soil moisture leads to more rain.

Take-Away

We’d be lying if we said we weren’t seriously worried about where this summer is heading for the Front Range. Heck, we’re already in a dire situation following nine weeks with very little rainfall. And now we’re staring down a developing La Niña — a pattern that historically erodes the summer monsoon, lessens the hurricane activity in the eastern Pacific and raises the thermometer here more than 2°F on average above our already hot summertime readings. Climate models and climate experts all agree that this summer is likely to be hot and dry in our area. As we’ve seen, the 2024 Colorado monsoon outlook is not a great one and the implications will be exacerbated by the dry fuels and soil already found across Front Range right now. At some point here soon, fire season is going to take off across the West, with wildfires spawning closer to home this year than more recent, wetter summers.

All things considered, it’s likely to be a hot, dry, fiery and smoky summer ahead. Remain vigilant with your sparks, flames, fireworks and camp fires. We’re going to need a little luck on our side to dig out of a worsening drought and see wildland fuel conditions recover. At this point, we are expecting the worst for this summer, but are hoping for the best.

Get BoulderCAST updates delivered to your inbox:

Enjoy our content? Give it a share!

Daily Forecast Updates

Get our daily forecast discussion every morning delivered to your inbox.

All Our Model Data

Access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather model graphics. Seriously — every one!

Ski & Hiking Forecasts

6-day forecasts for all the Colorado ski resorts, plus more than 120 hiking trails, including every 14er.

Smoke Forecasts

Wildfire smoke concentration predictions up to 72 hours into the future.

Exclusive Content

Weekend outlooks every Thursday, bonus storm updates, historical data and much more!

No Advertisements

Enjoy ad-free viewing on the entire site.

You must be logged in to post a comment.