The arrival of the North American summer monsoon varies substantially from year to year, depending greatly on the weather patterns of Mexico, the southeast USA, and the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean. We don’t have to wonder anymore — the monsoon has already commenced in the last few days, about two weeks ahead of schedule. Hooray! We discuss the current state of the monsoon, what’s happening with that pesky La Niña, and what to expect in the coming months across Front Range Colorado.

Key Highlights from This Post:

- Monsoon season has officially commenced ahead of schedule with a surplus of moisture already flowing into the Four Corners region

- Against all odds, La Niña is favored to persist through the summer and possibly through the winter ahead — this would be the third La Niña winter in a row

- During La Niña, the monsoon is usually suppressed southward leading to hotter and drier than normal conditions across the Front Range

- This hot/dry outcome for Colorado is also being predicted by climate experts, historical analogs, and climate model forecasts

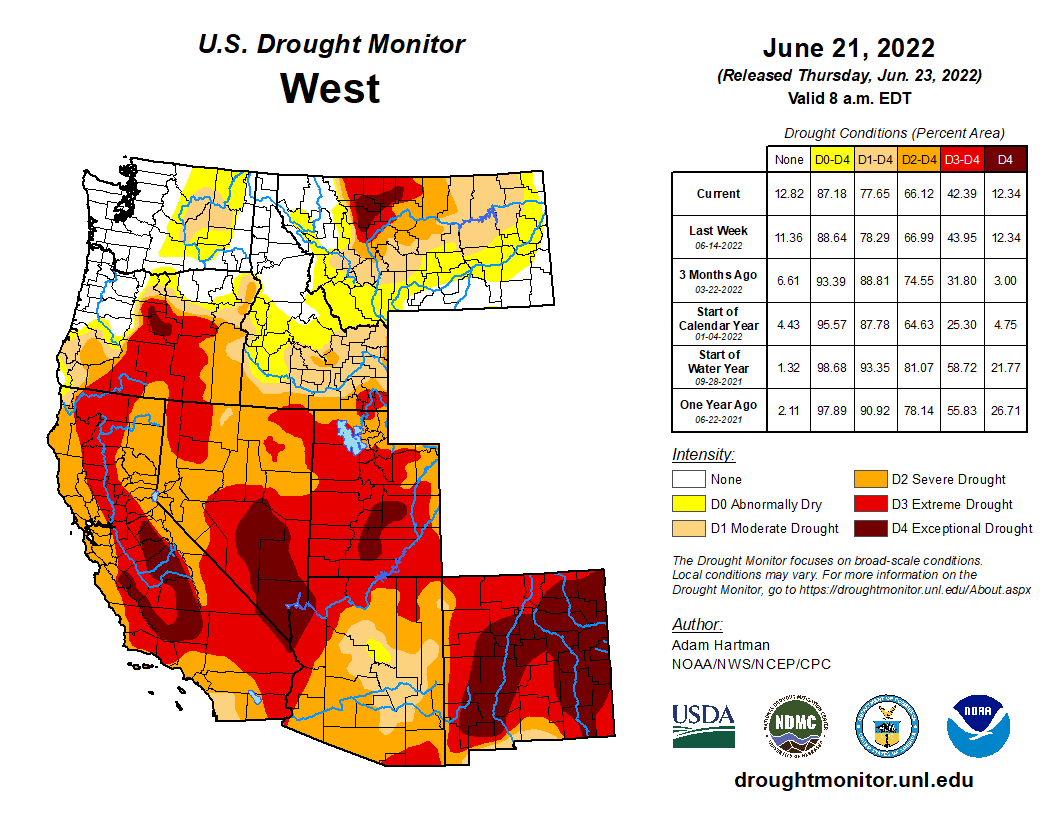

- Drought, which has improved somewhat of late, is expected to intensify further across the state in the coming months

- With severe drought encompassing much of the West right now, a devastating wildfire and smoke season likely lies ahead

We discuss Boulder and Denver weather every single day on BoulderCAST Premium. Sign up today to get access to our daily forecast discussions every morning, complete six-day skiing and hiking forecasts powered by machine learning, access to all our Front Range specific weather models, additional storm updates and much more!

Monsoon Update

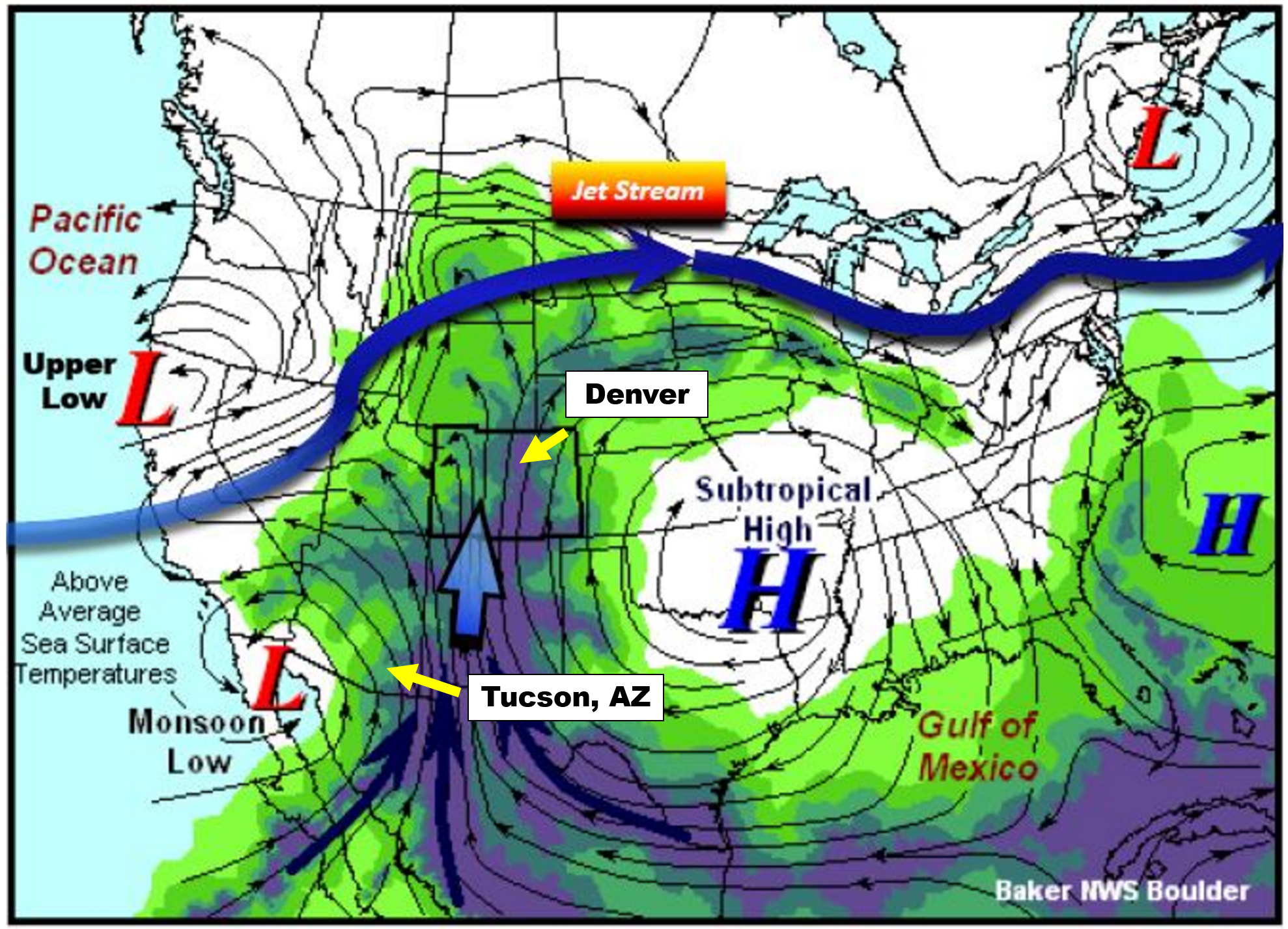

The diagram below shows the typical set-up for the North American Monsoon, the seasonal wind shift that brings soaking rains to Colorado and much of the Four Corners region each summer. A “monsoon” low pressure in southern California often teams up with high pressure in the southeastern United States to funnel relatively large quantities of low and mid-level moisture northward into the Desert Southwest. This moisture is key to forming the widespread monsoon thunderstorms that are a staple of Colorado’s summer. The storms form via daytime solar heating — with the clouds and thunderheads forming over the terrain first due to the sloped mountain surfaces heating up quicker. As the storm clouds grow in the High Country, the prevailing winds from the west or southwest push the storms eastward across the Denver Metro area where outflows can help form subsequent new thunderstorms. Each evening, all of the activity generally dies out shortly after sunset. This diurnal cycle rinses and repeats all summer long, with the ever-changing influx of moisture content determining the exact location and coverage of the storms on any given day.

Monsoon set-up diagram | NWS Boulder

One way that we can track the arrival of the North American Monsoon is to monitor surface dew points in southern Arizona. Cities like Tucson (see location above) are much closer to the source of the moisture than we are here in Denver. The moisture more-or-less has to pass through Tucson as it moves northward into the United States. Tucson is also a pivot-point for the moisture plume itself. Think of Tucson as the “faucet”, with a “hose” of moisture wandering northward. Sometimes the hose if over Nevada, other times it meanders over Utah, and Colorado as well.

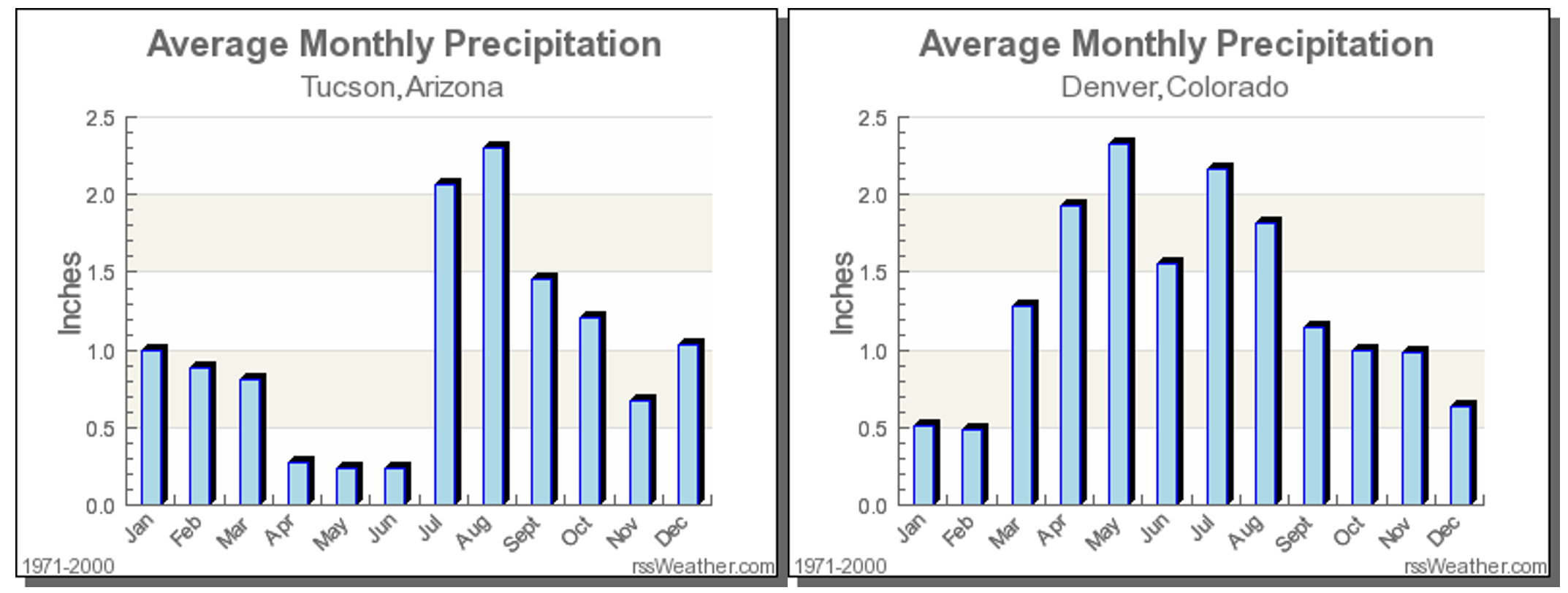

While our monsoon here in Denver and Boulder is sporadic throughout July and August, the faucet is nearly continuous for Tucson. For this reason, Tucson actually sees more monsoon rainfall than Denver on average, and has a more predictable and consistent monsoon climatology.

It is largely agreed upon that monsoon season’s official start is when the average daily dew point in Tucson is at least 54 degrees for three consecutive days. Seriously, this is a real thing that is closely monitored by meteorologists and residents of that area. We can’t blame them…July’s average rainfall exceeds the total for March, April, May and June COMBINED in Tucson (above plot on the left). The monsoon is a much bigger reprieve for them than it is for us, especially considering the edge it can take off of those 110-degree afternoons that frequently occur in the Desert.

The graph below shows the daily average dew point values at Tucson Airport so far this summer. The red line is the actual data from 2022. The gray line is climatology and the green line is the coveted 54-degree threshold for the monsoon.

As you can see from the graph, the last ten days or so have seen well above normal moisture flowing into Tucson at the surface. The official start on monsoon season came back on June 24th, the third consecutive day with values above 54°F. This is about 2 to 3 weeks earlier than the climatological normal! This early arrival doesn’t necessarily mean much. The end of monsoon season can fluctuate as well, but typically falls in mid-September for Tucson, and about two weeks earlier in Colorado. Along with the increased chance of daily thunderstorms, the monsoon brings more dangerous alpine hiking conditions, frequent evening rainbows, warmer nights, more lightning strikes to spark fires, and “stickier” air overall. After today’s borderline-scorching heat, we’ll all be ready for it!

La Niña Update

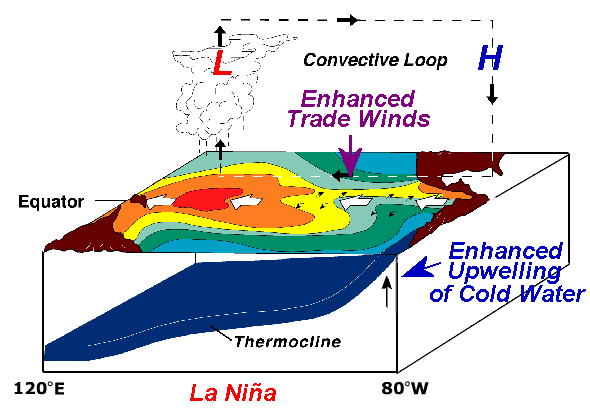

Remember that La Niña is associated with cooler than normal sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, with enhanced easterly trade winds along the Equator and a shift of the warmest waters westward in the Pacific towards Polynesia.

Large-scale upward motion in the atmosphere and the resulting thunderstorm development along the Equator follow the warm pool in ocean water westward. This creates a convective loop across the expansive Pacific Ocean from west to east (shown above). These are just the localized effects of La Niña. Our atmosphere and ocean are intimately coupled on a global scale. This altered circulation on the scale of the massive Pacific Ocean leads to locations all around the world, including Colorado, being influenced by ENSO in one way or another.

For better or for worse, we just completed our second La Niña winter in a row. Typically the ocean’s waters will even out in spring and summer months with both El Niño and La Niña rarely able to persist into June. That dissipation is exactly what happened last year with La Niña fizzling out in April 2021 with an ENSO-Neutral setup taking hold during the summertime months.

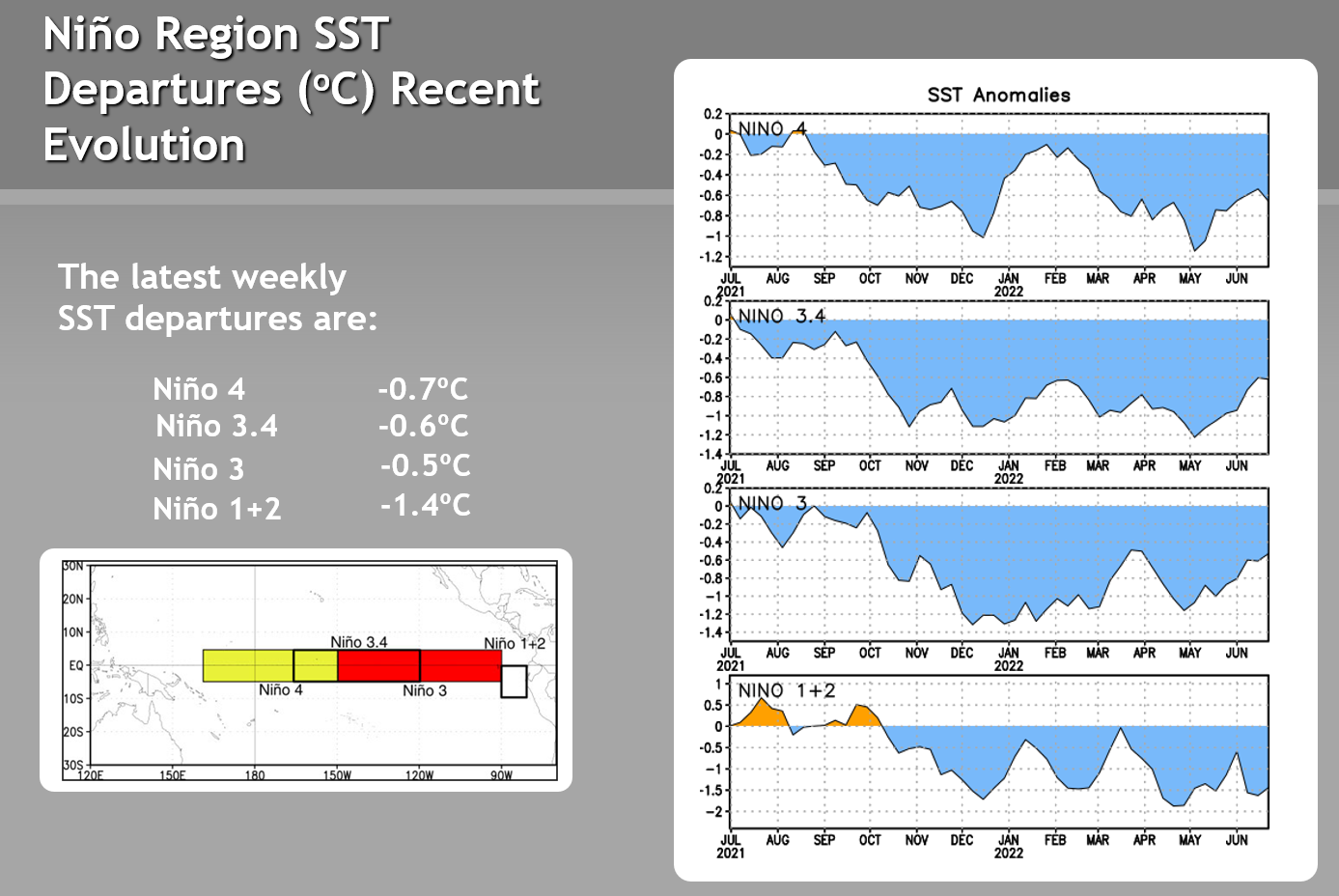

However, this year is different. The cold sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific Ocean have remained persistent thus far. Notice in the plots below how the cold anomalies have largely stayed the course in the various regions of the Equatorial Pacific. Niño 3.4 is the one most often used for determining the state of La Niña, which is defined as a value of -0.5°C or lower. In this case, we see that Niño Region 3.4 bottomed out in early May around -1.2°C, and as of writing remains in La Niña territory at -0.6°C.

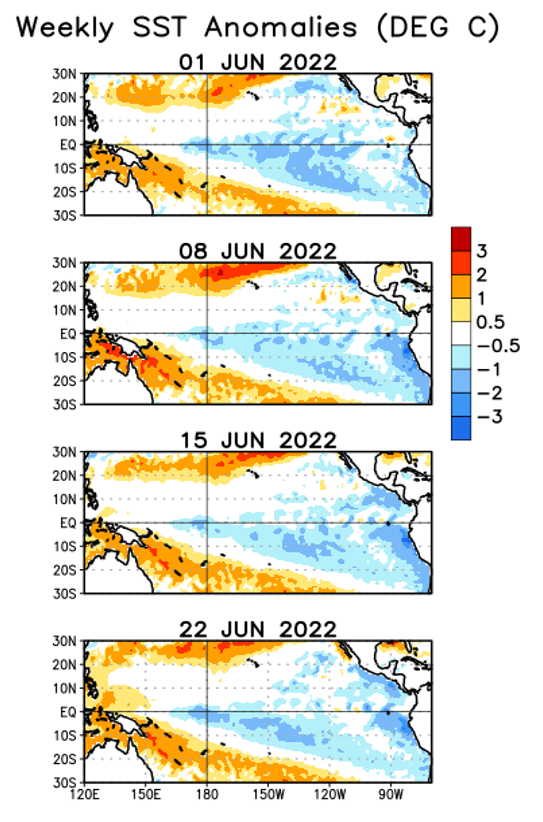

Looking at the evolution of sea surface temperature anomalies over the last month across the Pacific, not much has changed. Mostly we have seen a slight weakening of the cold anomalies in the central Pacific, while the waters cooled substantially over a narrow region along the coast of South America. That more or less agrees with the time series graphs above.

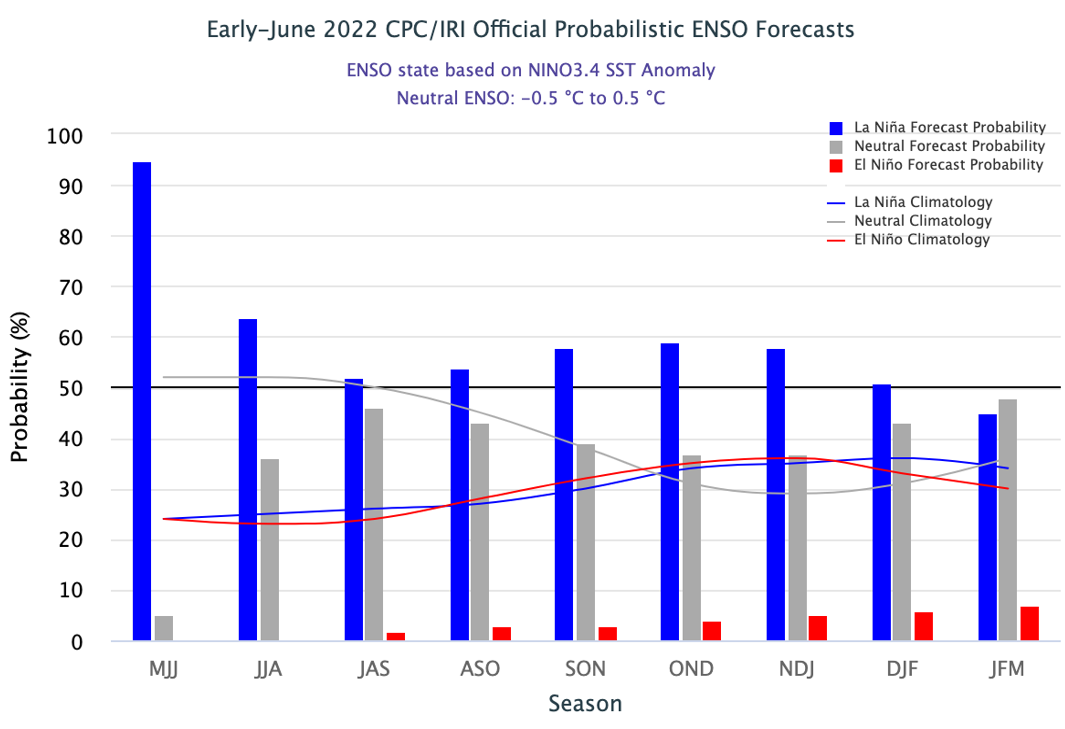

The key takeaway here is that La Niña is still very much active as of late June 2022. Based on official forecasts, La Niña is the most likely ENSO pattern to persist through the upcoming summer and even the distant winter ahead. If that comes to fruition, it would be our third La Niña winter in a row, something that hasn’t happened since the turn of the century (1998-2001). Furthermore, around August it becomes roughly a coin flip as to whether La Niña holds or if there will be a shift back to ENSO-Neutral. A small light at the end of the tunnel, perhaps?

Nonetheless, La Niña sticking around for the summer is generally bad news for the Front Range and most of Colorado. This is because the summer monsoon pattern is often suppressed further south during La Niña, whereas El Niño amplifies the reach of the monsoon into Colorado. Let’s walk through some data to confirm this.

Summer 2022 Outlook

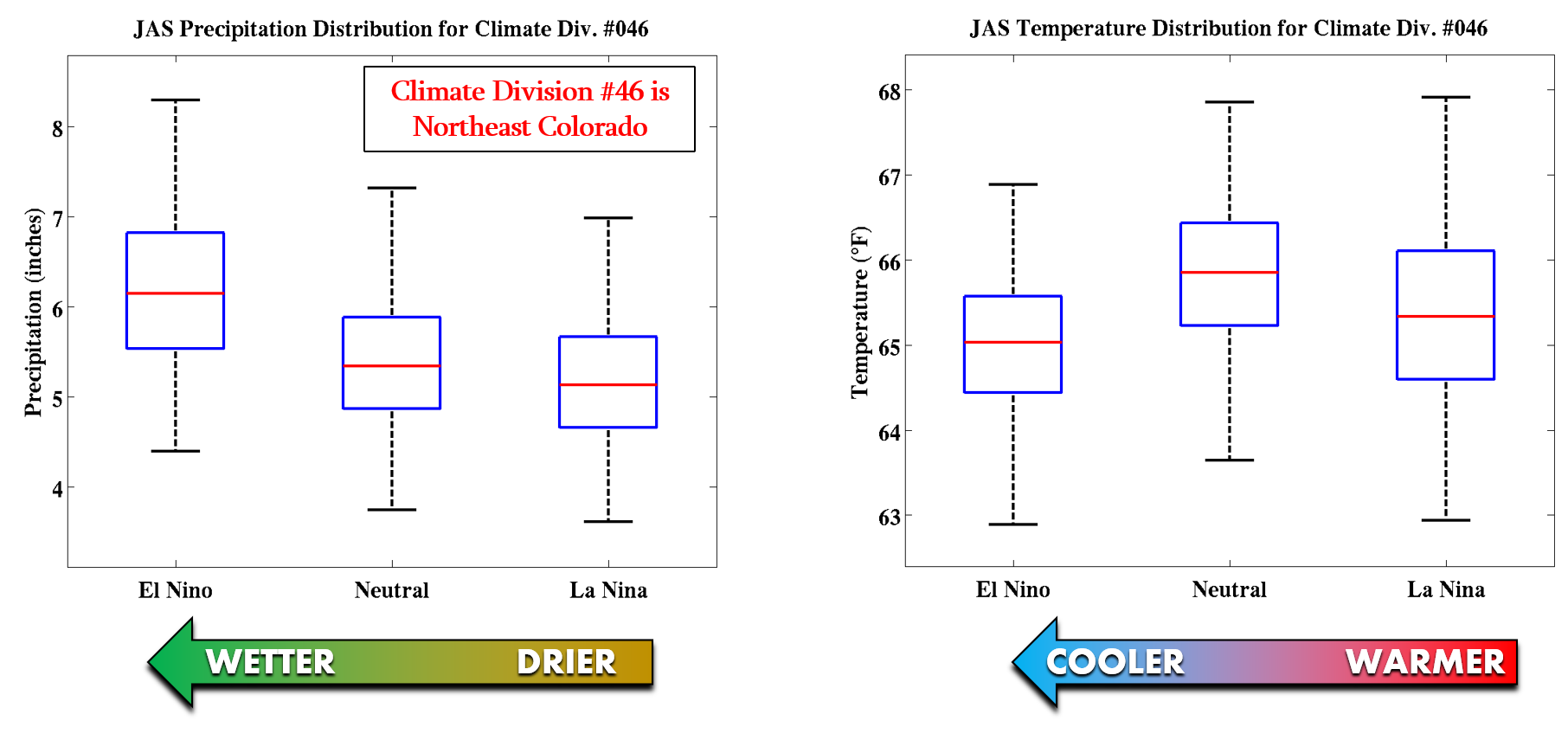

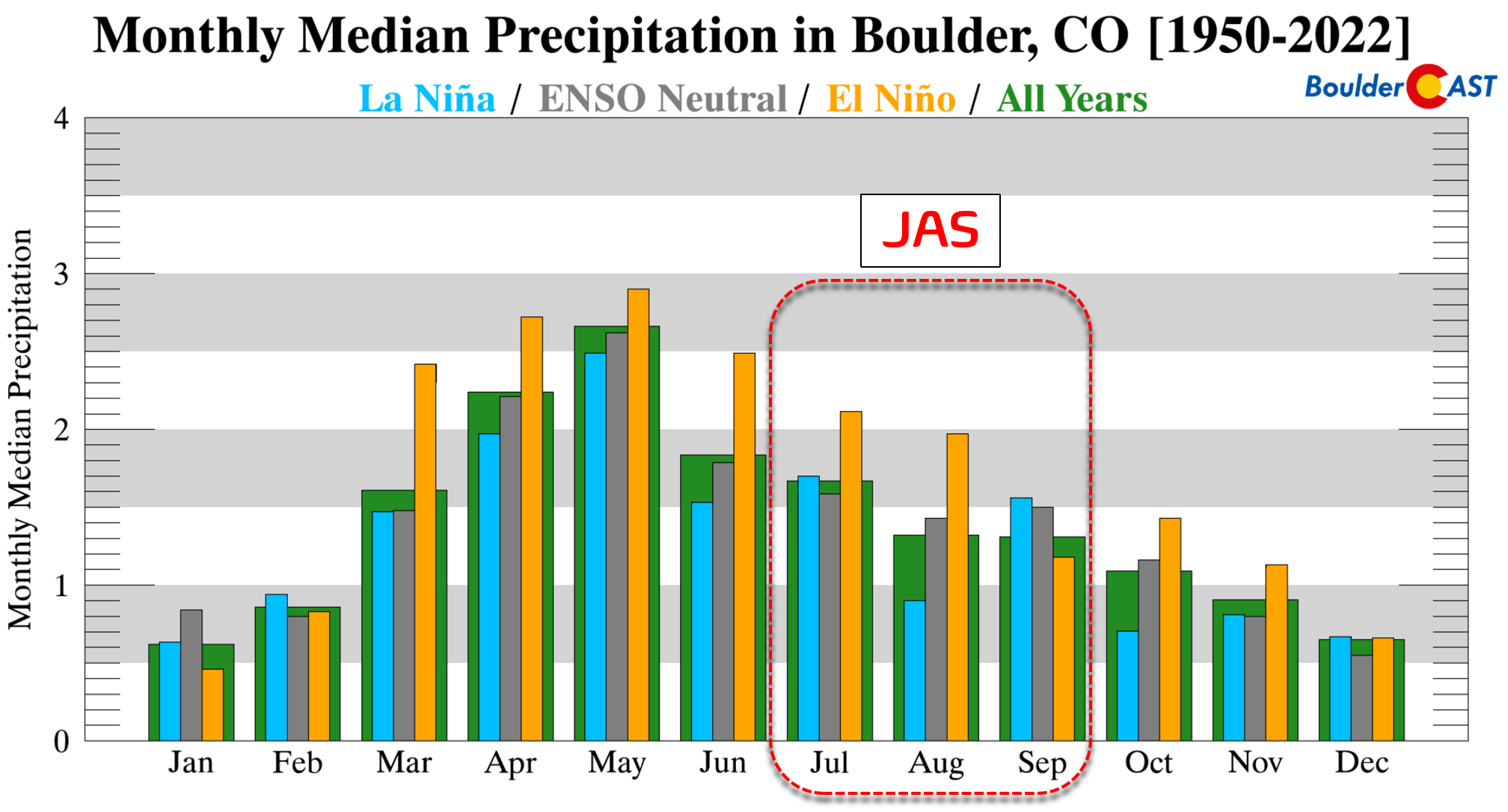

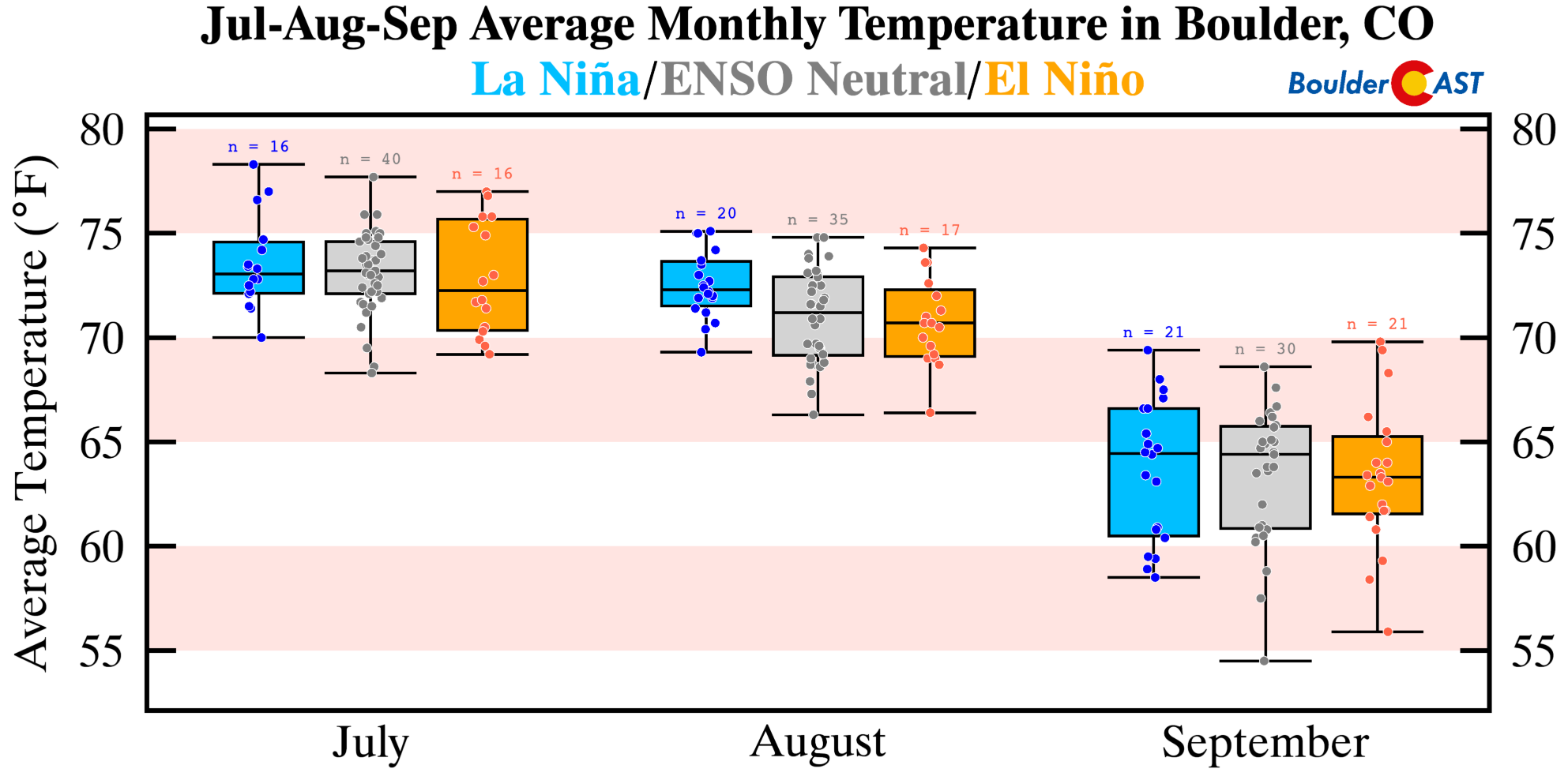

Shown below are box-and-whisker plots of precipitation (left) and temperature (right) for Climate Division #46 during the various phases of ENSO for the months of July, August and September (JAS). This is essentially the region comprising northeast Colorado and also some of north-central Colorado. A clear trend is evident from warmer and drier conditions during La Niña towards wetter and cooler conditions during El Niño. The shift in outcomes when going from La Niña to ENSO-Neutral, like some forecasts are showing, would help our area with a better chance to see more precipitation than if La Niña persists.

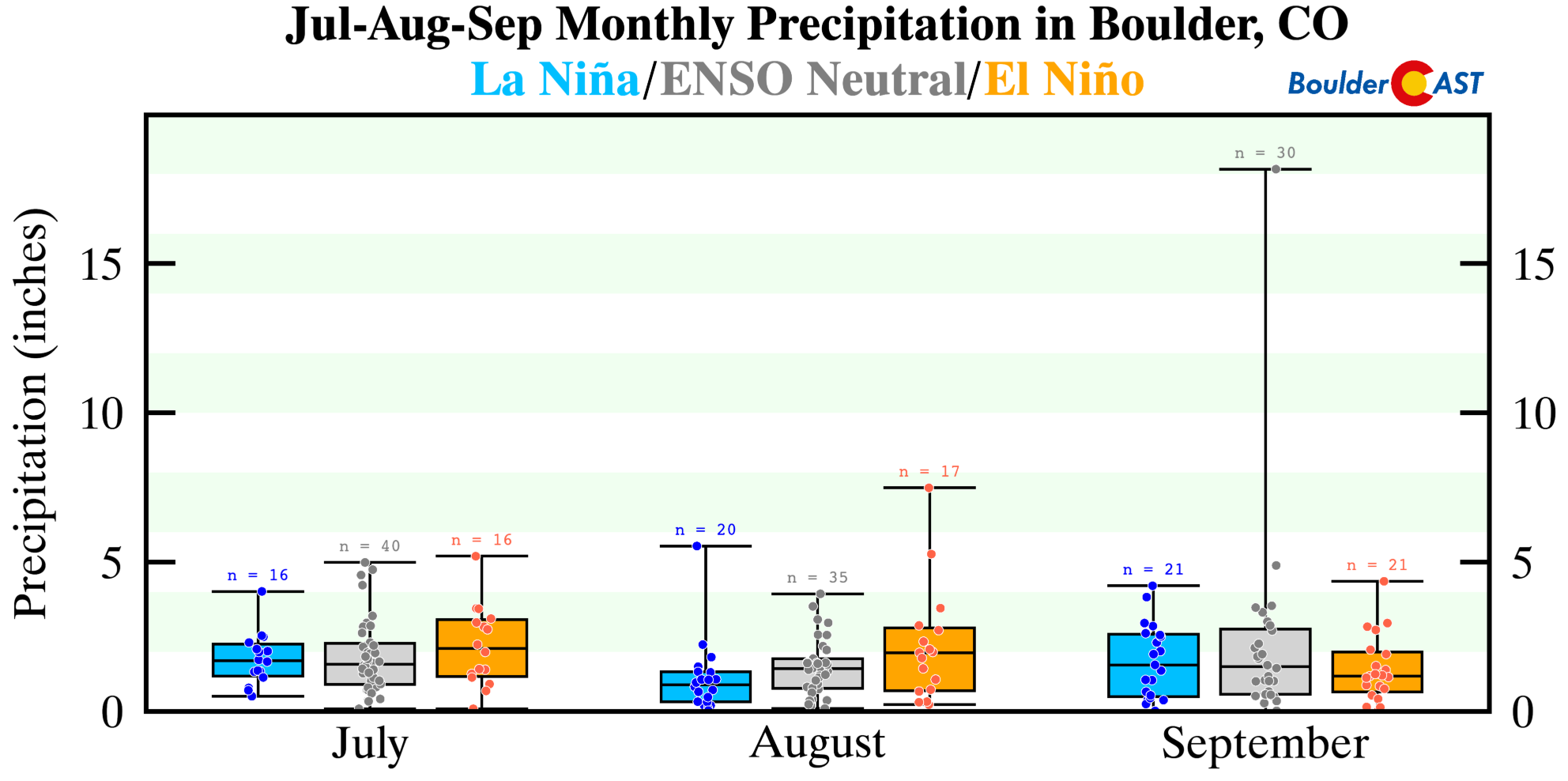

If we look at the historical data just for Boulder, we see the same trend in summer-time precipitation. July and August (peak monsoon months) are notably drier during La Niña compared to El Niño, though that trend reverses in September. Apologies….this precipitation graphic is a bit harder to read due to a single extreme data point. Yes, we’re referencing the 18 inches of rain that fell in Boulder during the 2013 Flood!

Total precipitation amounts in JAS decline nearly 30% during La Niña compared to El Niño. Here are the median precipitation amounts for JAS in Boulder:

- La Niña: 4.1″

- ENSO-Neutral: 4.5″

- El Niño: 5.7″

Switching gears over to temperatures, we note the same trend in Boulder that we saw earlier for all of northeast Colorado. More frequent monsoon clouds and thunder showers during El Niño take the edge of the scorching summer heat so common in the High Plains of eastern Colorado. El Niño summers are notably colder by 2 to 3°F overall in Boulder. However, on average ENSO-Neutral summers have more similar temperatures to La Niña summers.

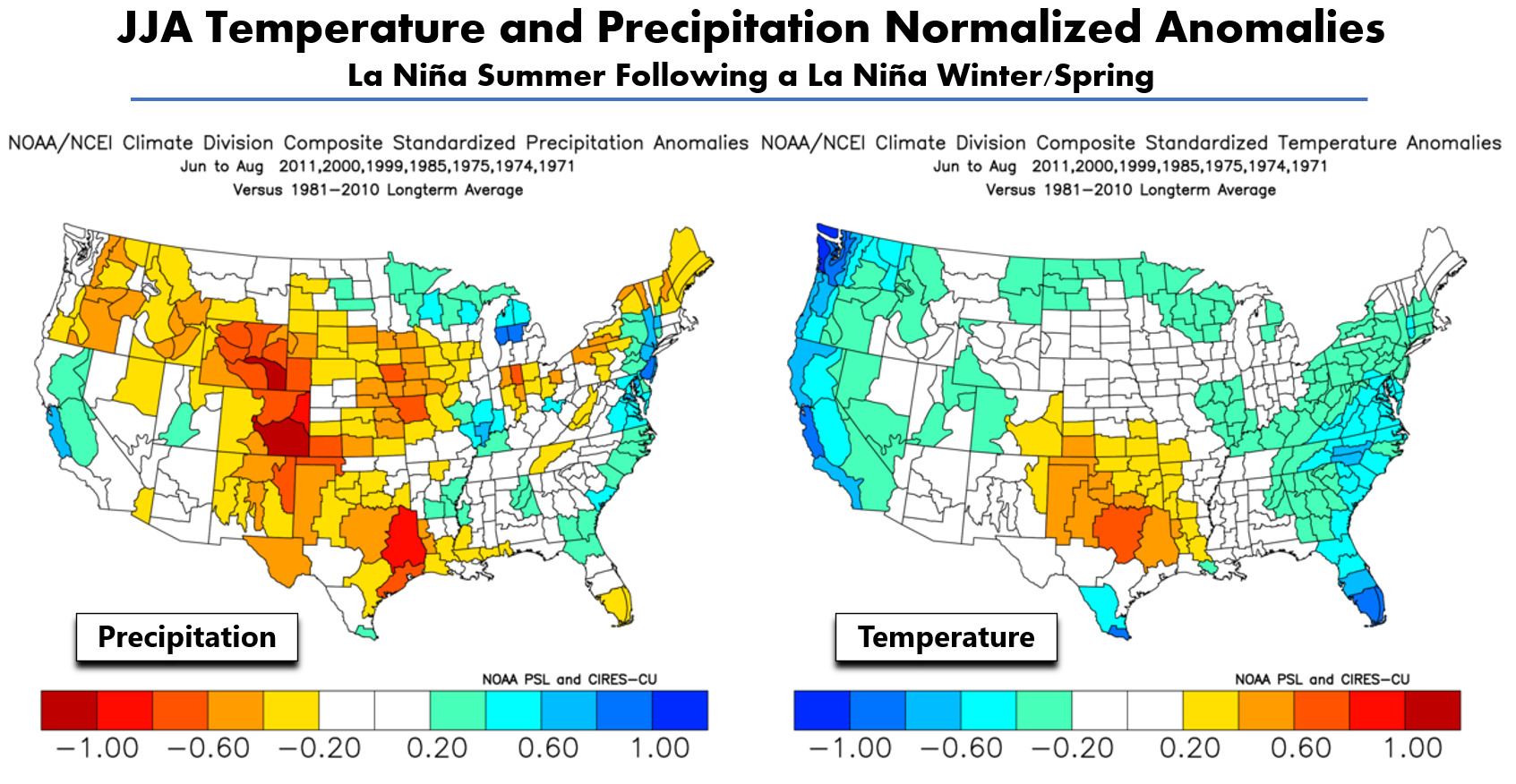

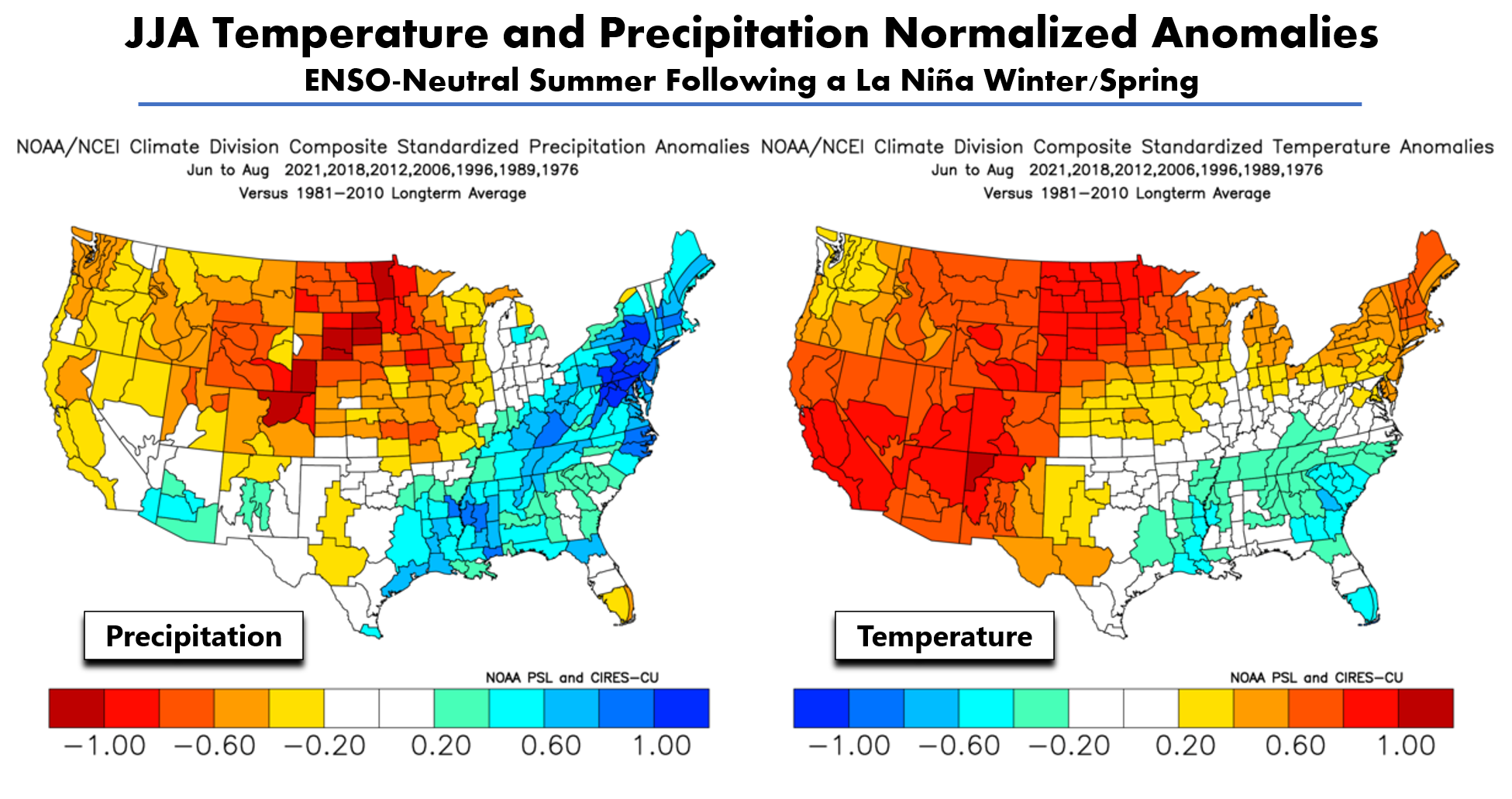

So far, looking at data generally pertaining to ENSO patterns, we would expect a drier and warmer than normal next three months (July through September). We can’t stop there though. Let’s take a quick check of the historical analog patterns relevant to the current situation. Shown below are JAS anomalies of precipitation (left) and temperature (right) for La Niña summers following a La Niña winter. These are the anomalies we might expect if La Niña were to persist through the upcoming summer, which seems likely. Note the very dry signal for all of Colorado in addition to many other western states that also depend on the monsoon. Temperatures for northeast Colorado in this situation generally stick close to normal or slightly above.

If somehow La Niña does weaken soon shifting us into ENSO-Neutral for the tail-end of summer, the analog outlook actually gets worse for the Front Range. Based on seven occurrences of this type of ENSO shift in the last 50 years, the future would be bleak for Colorado. A very strong hot and dry signal is indicated across the entire state. The most recent analogs for this situation are 2021, 2018 and 2012. All of those summers were extremely warm and dry for Colorado. If you recall, 2018 had almost no monsoon season whatsoever. And we all know what happened last year in the many months leading up to the devastating Marshall Fire.

So far we have reviewed the outcomes from past summer seasons, and nothing more. Remember, as with most of weather, nothing is ever set in stone. ENSO is a global indicator that just gives us hints about conditions that are slightly more likely to occur in the months ahead. The “randomness” of Earth’s complicated weather patterns from year-to-year is much more dominant on our weather than ENSO could ever be!

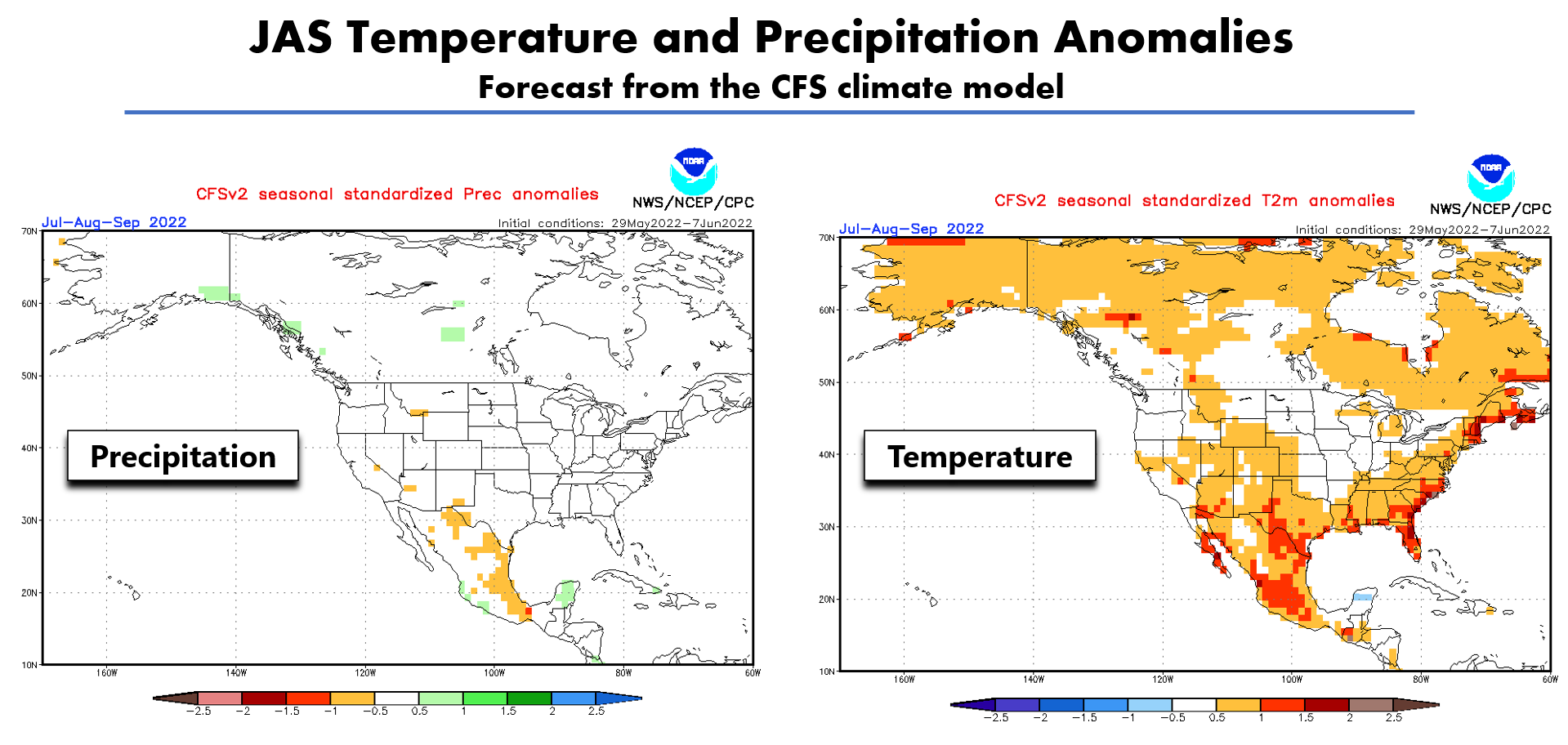

With that said, let’s take a look at actual forecasts. First, the prediction from a popular climate model, the CFS. This model is predicting a warm summer for most of North America (below right). For precipitation (below left), the CFS model is predicting basically near-average precipitation for much of the country. There are just a few hints of dry weather across the Desert Southwest, perhaps picking up on the likely disappointing monsoon season ahead for the Four Corners.

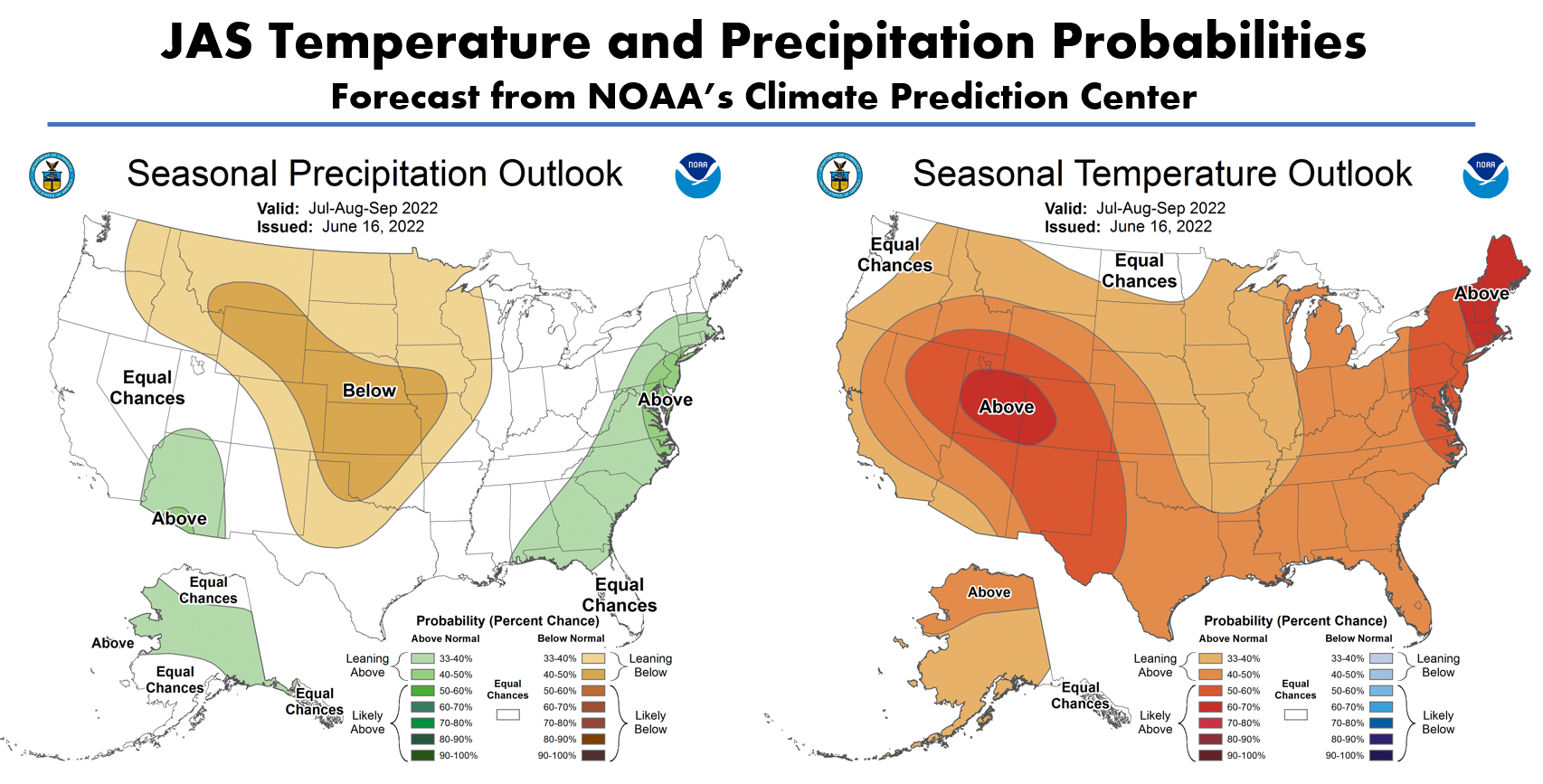

Below is the latest JAS forecast from the Climate Prediction Center. They are expecting elevated chances of a dry summer in the center of the country, including Front Range Colorado, as well as increased chances for warmer than normal temperatures for nearly the entire United States. The strongest warm signals are present over portions of Colorado and in New England. Wet weather is favored along the East Coast, as well as in Arizona where monsoon season is actually more intense during La Niña and ENSO-Neutral conditions. Overall, their forecast matches okay with the CFS model solutions, the situational analogs we showed earlier, and our general thinking about how the rest of summer will play out as a whole.

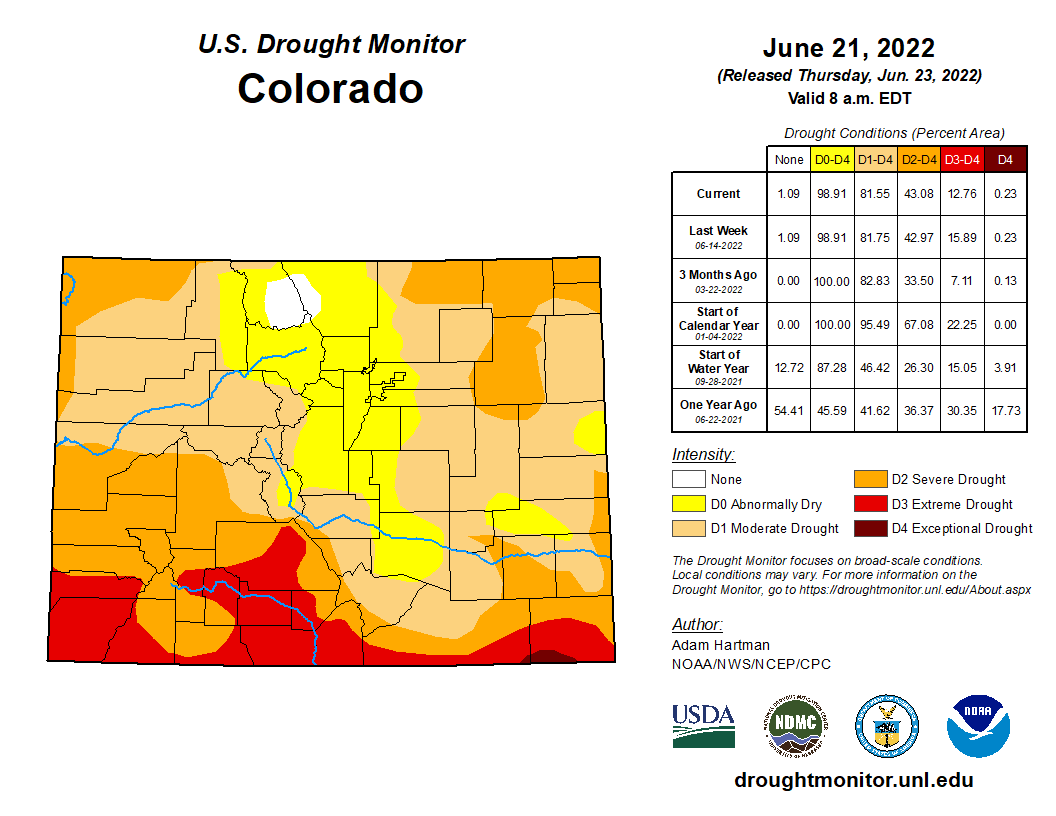

There has been some positivity around the improving drought recently, especially during the month of May when a couple of soaking rain and snow events pummeled the area. The recent improvement in the drought around Denver and Boulder is welcomed, but let’s not get too excited. Since early May, it’s true that we’ve seen a complete eradication of drought over much of the Front Range. However, we still are abnormally dry. Furthermore, western and particularly southern Colorado remain deeply entrenched in crippling drought. Unfortunately these are some of the areas most susceptible to wildfires. The anticipated lackluster monsoon, combined with record levels of tourism under the waning pandemic, may not bode well for our forests and grasslands — both of which are giving off strong tinderbox vibes right now.

Finally, let’s not forget what’s going on elsewhere in the West. Just about every other state has some form of catastrophic drought ongoing at the moment. With Colorado residing downwind from all of these states, we’re likely to endure yet another smoky summer, regardless if it’s our forests burning or theirs…

Get BoulderCAST updates delivered to your inbox:

Help support our team of Front Range weather bloggers by joining BoulderCAST Premium. We talk Boulder and Denver weather every single day. Sign up now to get access to our daily forecast discussions each morning, complete six-day skiing and hiking forecasts powered by machine learning, first-class access to all our Colorado-centric high-resolution weather graphics, bonus storm updates and much more! Or not, we just appreciate your readership!

Enjoy our content? Give it a share!