Even with thick high-level clouds overhead, yesterday saw “Fair” weather conditions reported across the Metro area, but what does this actually mean? As it turns out, “Fair” weather can signify a lot of things, with one critical caveat.

Though warm, yesterday turned out to be a rather gloomy day across the Front Range with thick high-level clouds filling our skies. The reason for the cloud-cover was the presence of upper-level moisture streaming into Colorado from the Pacific. The visible satellite loop below from GOES-East shows the clouds and their moisture source off the coast of Baja California.

GOES-East visible satellite loop for Monday morning (April 16, 2018) across the southwest United States.

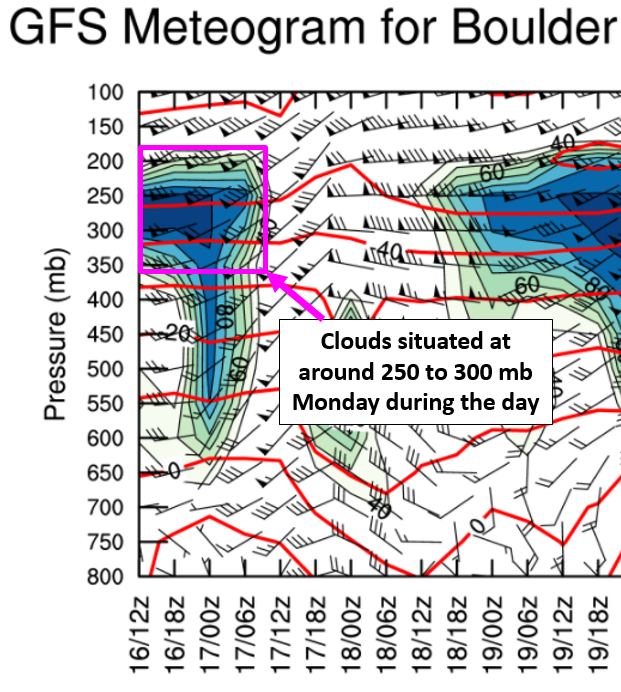

This moisture was well forecasted by the GFS model. The time-height plot for Boulder below has relative humidity contoured in blue coloring. The darker blues denote greater than 80% relatively humidity in the atmosphere and would be expected to be clouds. The GFS projected the height of these clouds to be between 250 and 300 mb in the upper atmosphere. This pressure level is very high…around 10,500 meters above sea-level or about 8,900 meters above the ground in Boulder.

GFS time-height plot of winds (barbs), relatively humidity (blue-filled contours), and temperature (red lines) for April 16-19, 2018.

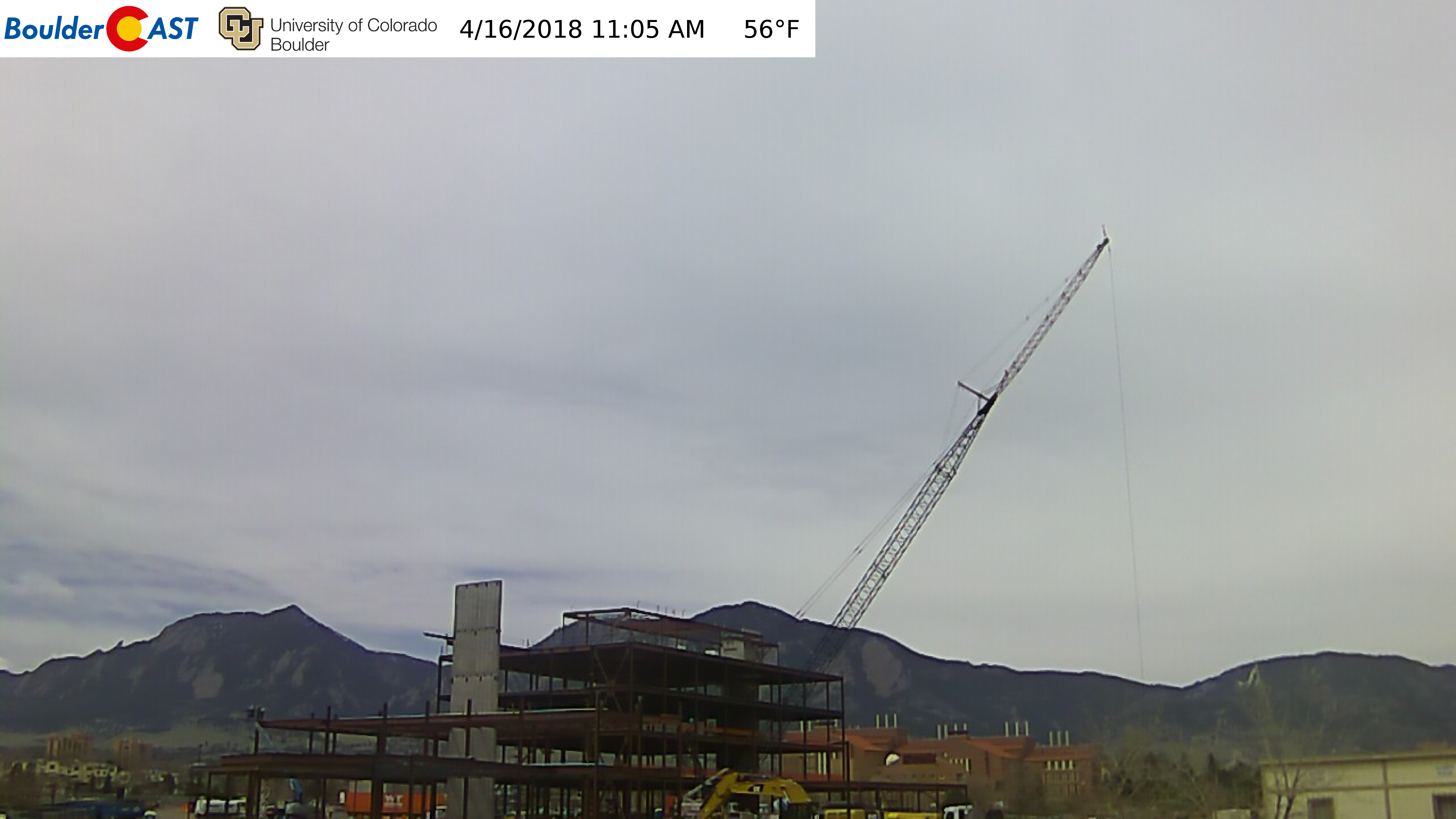

Webcams from around the region matched up nicely with the satellite imagery. It was an unusually cloudy day Boulder:

And in Denver:

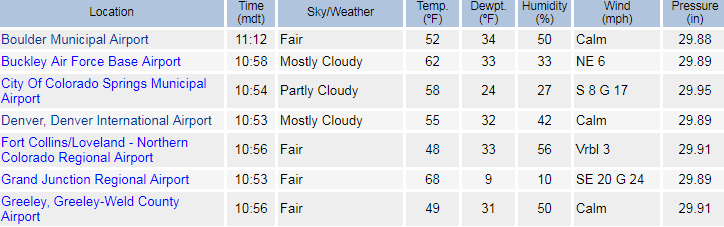

However, during this time, many weather observations from across the region generally reported “Fair” conditions. Here is the look at what several local airports were displaying late Monday morning:

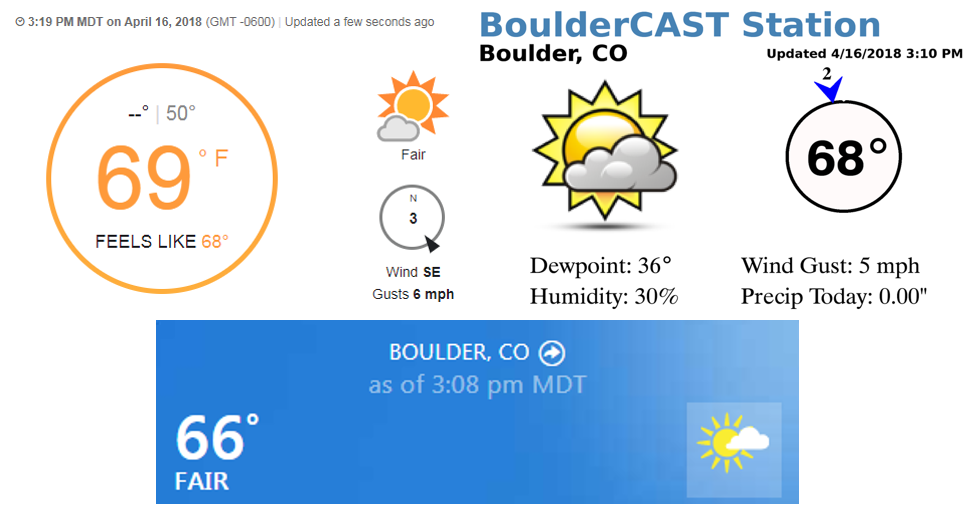

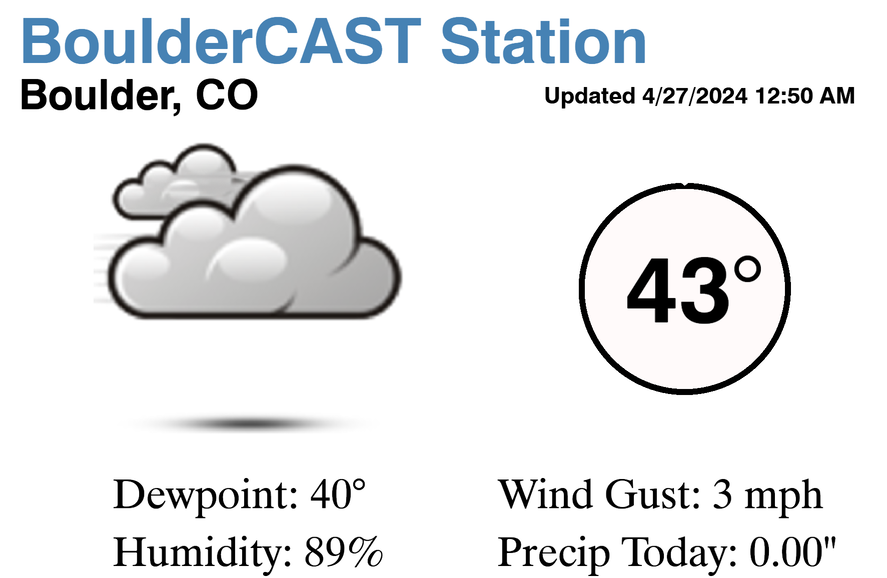

Below are a few observations taken directly from local weather sources on Monday afternoon for Boulder. At BoulderCAST, we don’t actually spell-out the current observation in text, so we don’t explicitly show “Fair” as the condition. However, the “Cloud+Sun” is the icon we use when “Fair” is reported. Trust me on this one…

Weather observations as reported by….Top left: Weather Underground | Top right: BoulderCAST | Bottom: The Weather Company

Obviously the skies were filled with thick clouds, so what does “Fair” actually mean? Why was “Overcast” not being reported instead? Meteorology background aside, I personally would expect “Fair” to be synonymous with “Sunny” or “Clear”. This is somewhat true, but “Fair” conditions require all of the following conditions be met:

- No precipitation occurring

- Very light or calm winds

- No major visibility reduction

- No extreme cold or heat

- Less than 40% of the sky has cloud cover*

In theory, based on the information above, “Fair” basically just means nice, calm, or pleasant weather. Sure, we can all get on-board with that! However, yesterday did NOT have less than 40% of the sky covered in clouds. There was in fact 100% cloud cover almost all day! This conundrum is where the big red asterisk comes into play. See, most weather observations in the United States are actually done by automated weather observing systems (known as ASOS or AWOS stations). Sky cover from these automated systems is probed by an instrument called a ceilometer (pronounced seal-aww-meter), which is just a fancy type of laser pointed straight upward at the sky. The standard ceilometer has a maximum measurement range of 7,500 meters…meaning any clouds that are higher than 7,500 meters above ground will not be detected by the ceilometer and the automated system will report that there are no clouds.

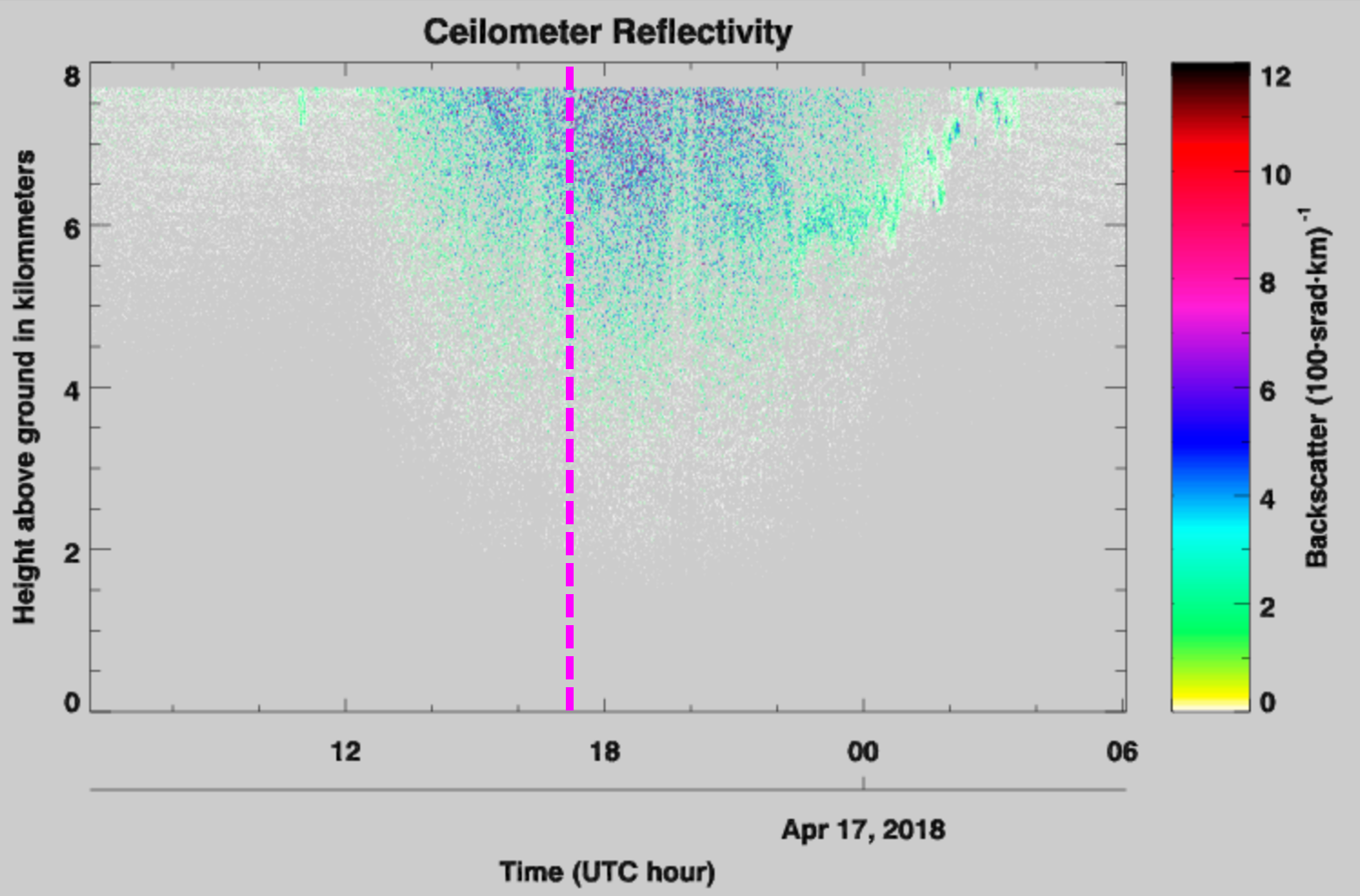

Remember from the GFS relative humidity plot we showed earlier, the clouds yesterday were forecasted to be near 8,900 meters, just beyond the range of the ceilometer is able to detect. We don’t have to rely on the model forecast cloud height, however! The ATOC Department at CU has a ceilometer operating in Boulder as part of the Skywatch Observatory. Shown below is the data from the ceilometer from Monday. The pink line shows the time the webcam images of cloudy skies were taken late in the morning. Of course, you’re not a ceilometer/lidar expert like me (my Greenland snow research included operating a ceilometer and analyzing the data). So despite the noisy backscatter signal present, there are no clouds detected by the ceilometer at this time. Although, there are some high clouds after about 00 UTC between 6 and 8 km detected. This was later Monday evening.

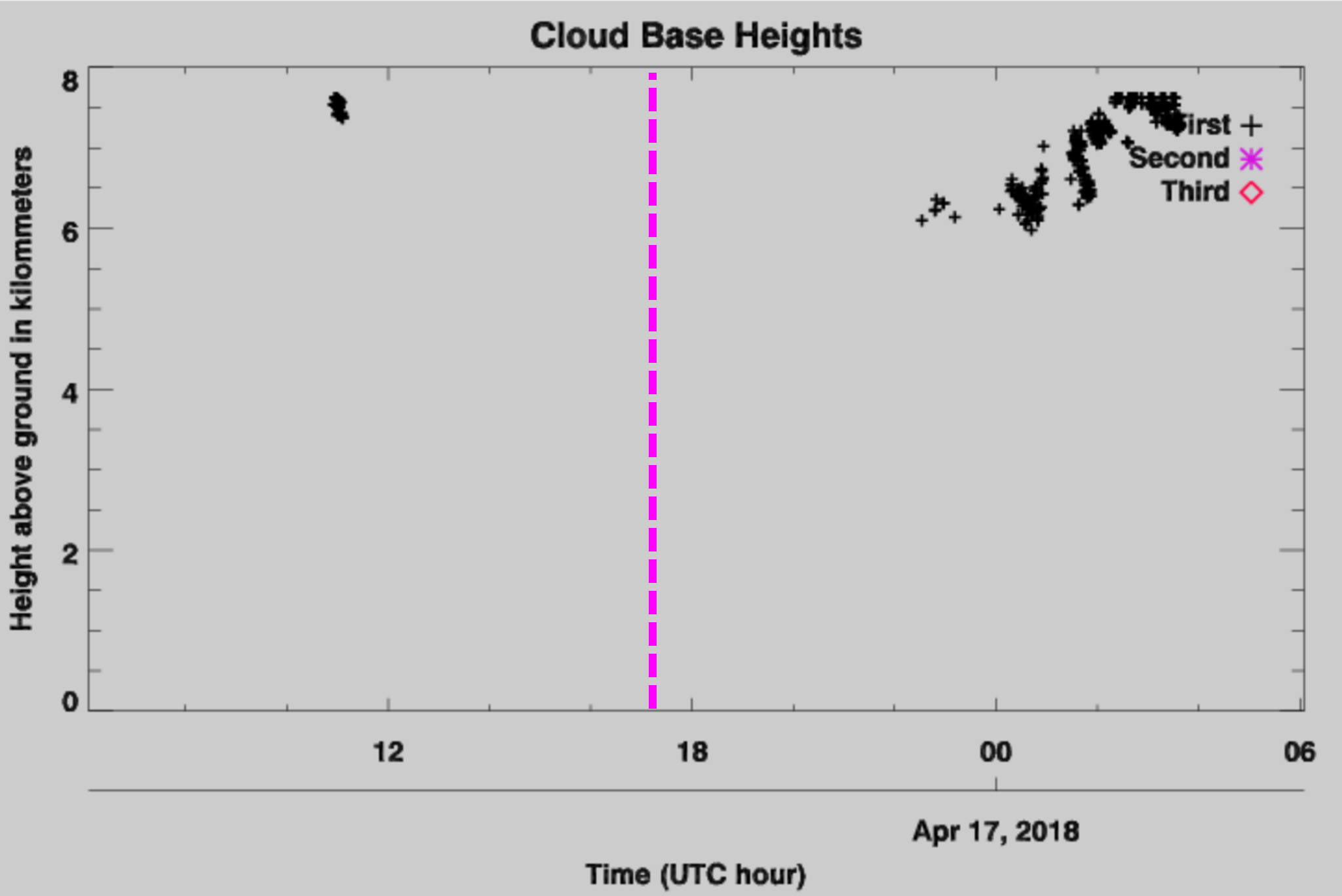

This is all slightly more evident in the “level 2” cloud base product of the ceilometer (below) which is derived from the reflectivity data profiles (above). We now see a few clouds detected earlier in morning, and more clouds later in the evening (black marks on the plot below), but nothing at the time the webcam images were taken.

So as you have seen, basically there is a limitation in our automated weather instrumentation that prevents high-level clouds from being detected, thereby triggering the “Fair” condition to be falsely reported. Unfortunately, being downwind of the Rocky Mountains, we often see these thick high-level clouds in the upper atmosphere forced in part by the terrain. This lack of adequate cloud-detection may actually be responsible for Denver’s notorious “300 Days of Sunshine” being a slight overstatement.

Don’t worry! The technology actually does exists to detect these higher clouds (space-borne cloud radars/lidars, ground-based cloud radars), but most weather observations are associated with airports and supported by limited Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) funding. Yes, we theoretically can detect these clouds, we just can’t afford to at the moment. Aircraft pilots really don’t care about high-level clouds anyways…it’s the lower ones that cause trouble for take-offs and landings. Some larger airports also have living, breathing meteorologists on staff to take manual observations. Go figure! The human eye is surprisingly skillful at determining whether clouds are present or not, and if conditions really are all that “Fair”…

Share this weather information:

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.