Over the course of my graduate studies at CU Boulder, my atmospheric research has taken me to one of the coldest and harshest places on Earth, central Greenland. I made the trip north four times over the course of just three years, studying cloud formation, snowfall, and weather patterns, among other things. Traveling to Greenland is something few people will ever get the chance (or possibly want) to do. Thus, I would like to share my experiences with you all by retelling my many Arctic adventures.

My story consists of posts derived from journal entries written in the past few years, many while I was actually in Greenland. I cut it down as much as possible, but there is plenty to share! This will be a three part series. Look for the second and third posts on the following two Fridays. Apologies if these posts come off a little more “bloggy” than the rest of our content. However, I can promise at least a few chuckles and that you will learn something new.

Some stories covered in the series:

- The first time my eyes froze shut

- My first time eating musk ox pizza, whale steak, and puffin legs

- A difficult decision to leave Greenland when I came down with a serious medical condition

- Photographing the Northern Lights at -70 degrees Fahrenheit

- A few sketchy landings and take offs from a runway entirely made of snow and ice that was shrouded in fog

- Interactions with Greenlandic Inuit peoples

- Are penguins really that soft? I wouldn’t know. Come on, those are only in the Antarctic

- Plenty of science

For me, the memories of my trips to the world’s largest island and second largest slab of ice will last a lifetime! Hope you enjoy the retelling of my freezing cold excursions! Who knows? Maybe one day you will dare to visit the great (almost) nation of Greenland.

NOVEMBER 2010

Choosing a Direction

It’s official. For the next several years of my life, I will be researching the rapidly changing Arctic climate system…specifically those influences related to clouds over Greenland. My adviser (boss) will be Matthew Shupe, a former University of Colorado graduate student himself and a scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) office in South Boulder. I was aware of this opportunity for almost two years, and it may have actually played a role in me choosing to attend Colorado for graduate study.

Along with the chance to work with Arctic data, comes the obligation to spend several months out of each year on-site in Greenland, one of the most remote and undiscovered places left on Earth! The location is nearly dead-center in the middle of Greenland, at a small research outcropping known as Summit, given this name because of it elevation, which is nearly 10,500 feet above sea level. Summit is at 73 N latitude, which means the Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) are visible across the sky on most nights. Because of the elevation and extreme north latitude, Summit almost never gets above freezing, and typically sees temperatures well below zero (less than -60 F) in the winter. Also, because of the latitude, at times around the solstices, Summit experiences 24-hour daylight (summer) and 24-hour darkness (winter). Let’s just say its a pretty unique place, much different from Colorado.

The project itself is funded by the National Science Foundation and has the catchy name: Integrated Characterization of Energy, Clouds, Atmospheric state, and Precipitation at Summit, or ICECAPS for short. Through the use of a number of cutting-edge remote sensing and in-situ instruments (radar, lidars, sodar, radiometers, ceilometers), our group will be examining clouds, precipitation, and atmospheric structure, all of which are poorly understood over the Greenland Ice Sheet. Clouds can have profound effects on climate and climate change by altering the radiative balance in the atmosphere and at the surface, and through their roles in converting water between vapor, liquid,and ice phases. An improved understanding of cloud structure and processes is vital to understanding climate change, especially in the Arctic where this climate change is evident as the ice sheet continues to melt. It has been proposed that the Arctic climate plays a significant role in the climate of lower latitudes, and is widely known that the first, most apparent evidence of global warming will be found in the Arctic Circle (bye, bye sea ice).

Currently there is not much I can do on the project, as I have little time with classes and teaching. However, I have begun to analyze some cloud data from Barrow, a city in far, far north Alaska that is also part of the Arctic climate system. I have been working on this at my own pace, and has served to introduce me to some of the same instruments I will be working with in the future. I will also be killing two birds with one stone, as I am using this research for a presentation and paper in my remote sensing class this semester.

Can’t wait for fall break, I mean homework/project/presentation/studying catch-up! Cheers!

Click to collapse this post

JUNE 2011

First Journey to the Ice

This is my longest post to date. Hope you make it though it all!

NOTE: Hyperlinks are included in the text for more information on the given word or topic…great additional reading!

THE JOURNEY TO!

After a long stint of pressuring the National Science Foundation, they finally agreed that it would be extremely beneficial for me to travel to Greenland this summer for ten days, before I take a 3-month trip in February 2012, in the dead of winter. I ordered my passport just twenty days before my scheduled departure date and it arrived promptly more than a week in advance. I began to gather insight from my boss at NOAA of what to expect from the trip. After being issued my extreme cold weather gear, purchasing a few last-minute winter accessories, getting sun screen and sunglasses, and jamming it all into a giant, 5-foot long blue duffel bag, I was ready to begin my excursion!

My trip began with a flight from Denver to Albany, NY where I met up with a few other students on their way to Greenland as well. We got dinner and took a taxi to our hotel, where we retired early in preparation for our 5AM start the next morning.

We were picked up early by the Air National Guard at the hotel and taken to their base in Scotia, NY, approximately 20 minutes away. Here we walked through a comical security checkpoint, which consisted of putting our baggage and anything metallic (i.e. assault rifles, knives, or swords) onto a table, walking through a metal detector, and getting our un-inspected belongings on the other side. After sitting in a room for about four hours, we boarded our plane for Greenland, an LC-130. These planes are so loud that you must wear ear-plugs while in transit. They also are not optimized for passengers, as they are mainly cargo planes. The picture pretty much sums up the 7-hour flight….uncomfortable and crowded. A long time later we landed at our destination, Kangerlussuaq, a small settlement in a deep, U-shaped glacial valley along a massive fjord in southwest Greenland. The airport here is the most frequented in the country, and the only one that can support large planes.

Kangerlussuaq has about 600 residents, made up of a mix of native Inuits and migrant Danes, most of whom are in some way or another affiliated with the airport. One of the locals who works at the airport commented to me that “We are only here to work at the airport and the airport is only here to take the us home to Denmark to see our families.” Though I got a good chuckle out of this, I know that this town is also the largest tourist destination in Greenland, for reasons I will discuss later, and also the major hub for all scientific trips like mine to the Ice Sheet.

The settlement has a very “small town” feel. Everyone passing by in cars smiles and waves. Most of the forty or so structures are painted in vivid colors, likely to freshen up a landscape that is either all white or all brown, depending on the time of year. A few of the town streets are crudely paved, but most are just dirt roads. The longest continuous paved road in Greenland has its origin in the western parts of the town. It spans a whopping 13 miles along the fjord’s shore to a small harbor.

I slept three nights in this building, which had running water and comfy beds… all you could really ever ask for from a Greenland “hotel.”

After arriving late afternoon on Tuesday, June 7th, we were treated to a buffet of local food, including rice, vegetables, and musk ox stew. I stayed in a place known as the KISS building (acronym shown in picture) which was basically a glorified hostel.

We explored the town a tad after dinner, then everyone retreated to bed, except me. I really was not that tired, still being on Mountain Time, it was only 5PM to me. I decided to head out for a hike and enjoy the weather. Contrary to popular belief, the coastal regions of Greenland are not really that cold (in the summer, at least!) and this particular day it was in the low 60’s. After talking to a few Danish men on the street, I decided to hike straight up the ridge behind the airport, starting at around 9PM local time. Because Kanger (as the town known, for short) is at 67 degrees north latitude and in the Arctic Circle, I did not have to worry about running out of daylight. The sun doesn’t set between May 30th and July 13th every year. The hike I took was pretty intense, though notably easier since I normally reside at 5,500 feet elevation in Boulder and Kanger is just slightly above sea-level.

I made my own trail to the top, zig-zagging my way up the steep hill. There were far more animal remnants along the way then I would have initially expected, but I guess it makes sense that decay is minimal in an area that is only above freezing three months out of the year. I reached a point which from town looked like the summit. However, I realized that the ridges kept getting progressively higher and higher for miles, like a massive terrace. On each level of the terrace there were small, frozen lagoons. In these small ponds, hanging out near and under the ice, were angry little lemmings which did not appreciate my presence. The were barking, flopping around shattering the floating ice, and overall they just gave me a bad vibe. They were also nearly impossible to photograph, as they stayed entirely under the mirror-like water surface the whole time. Soon after, I reached a location which I was satisfied with as calling the “summit.” What a view to behold!

The hike back down was significantly more challenging. I had not realized truly how steep it was when I was climbing. There is also no real footing here, as the soil consists only of very fine-grain glacial silt. The small amount of dead vegetation acted as stepping stones and eventually I made it back to Kanger and into bed by 1AM local time.

A view of two fjords coming together just east of Kanger from the “summit.”

The dirt pathway in front of me is an animal trail that I was following.

—

The next day was spent entirely around Kanger. My flight to my final destination, Summit, was not until the following morning. One of the frequent scientists to Greenland knew a guy that would rent out his truck. Does this sound shady? It was. Where would anyone go in Greenland in a truck, especially in a country with virtually no paved roads? You may remember I mentioned Kanger is the number one tourist location in Greenland. This is because the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet is only 20 miles away, down a bumpy and quite poorly maintained dirt/sand/rock road. A local tourist company repairs the road periodically, and therefore has taken it upon themselves to install a gate to keep free-loaders out. The location of a key to this gate is one of the closest guarded secrets in town. Seriously. You’d think there was something more valuable at the end of that road. Somehow, by a grace of God, we were able to get hold of the key. The car we rented was a circa 1990 Toyota truck. The gentleman who rented it out only wanted $140, and since we rounded up nine people to go, it only cost us around $15 each. The local tourist company charges nearly $200 per person to go on the exact same adventure. What a rip!

After some boring safety training in the morning regarding our trip to Summit, we were off down the road to the Ice Sheet. It was a very bumpy ride…everyone in the back had to hold on for their lives. Our driver, Von, a scientist in my group from the University of Idaho, pushed that little Toyota to its limits! On the way, we passed through glacial valley after valley. There were semi-frozen ponds and huge lakes everywhere.

We even managed to stumble across a half dozen reindeer (caribou) on the 20 mile trek.

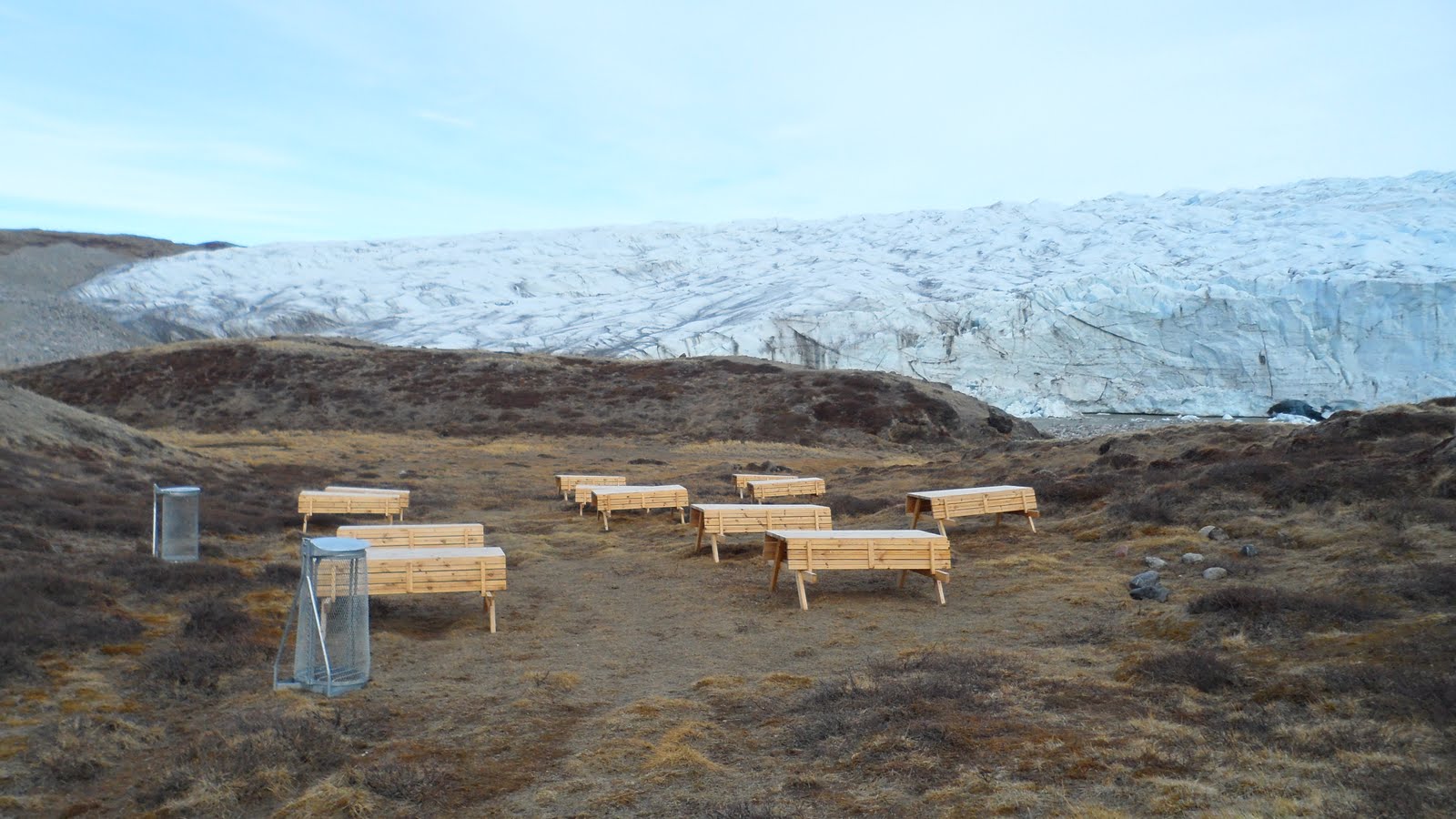

Finally, after over an 90 minutes, we reached the edge of the Ice Sheet! The texture on the ice near the boundaries is remarkable! The strong, cold breeze flowing off the edge of the glacier was refreshing. This persistent wind near the edge of the ice is called a glacier breeze, and is very similar in formation mechanism to a sea breeze.

We then proceeded to hike out onto the ice. Being in early June, the glacial melting had just begun. There were a lot of small melt streams forming on and near the ice, but no where near the magnitude there would be in early July.

Hiking on the ice sheet itself was surprisingly easy. The ice is not slick at all, and in most cases is very jagged and offers superb traction. The ice had the likeness of little white sand dunes — stretching as far as the eye could see. Huge mounds of silt, small rocks, and huge boulders can be see around the edge of the ice. These are called moraines and are basically what the glacier has “spit out” at its edges for thousands of years. It was a blast jumping across the little streams and attempting to not fall on the ice. After a few hours, we headed home, stopping temporarily at the Russel Glacier. The tourist company had set-up a very inviting picnic area. However, the wind was strongest and coldest here, so we opted out of eating dinner here and continued back to town to get some grub.

We decided to go to a (the only) local pizzeria. This establishment was operated by a jovial gentleman from Turkey. I got a good laugh knowing our Italian food in Greenland was being prepared by a Turkish man. I had heard nothing but good comments about this place, so when I tasted the food and it was delicious, it was not a surprise. I ordered a mozzarella, pepperoni, and musk ox calzone. You only live once, right?! Where else can you eat musk ox as a staple in your meals? I returned home and went to bed, anxious to catch the flight to Summit in the morning.

WELCOME TO SUMMIT!

I boarded another LC-130 for the two-hour flight to Summit. This time the Air National Guard was serious. The prior flight I had worn shorts with no problem. Now I was forced to wear (or at least hold) my ECW gear. You have to be prepared if the plane were to go down out on the ice. In Kanger it was near 60 degrees when we took off. At Summit, it was 20 below zero when we landed. What a temperature contrast! Getting off the plane, the first thing that ran through my head is, “Wow it is bright. Where are my sunglasses?” Typically at Summit it is cloudy (Trust me, I know. This is precisely what my research involves…when is it cloudy at Summit and why?). However, this day was particularly clear, with only a few small cirrocumulus clouds gallivanting in the southern sky. I could barely keep my eyes open. I pulled my sun glasses out of my pocket, slipped them on, and instantly felt a sense of relief.

A view of the Big House. The oldest building at Summit. The flags honor the cooperative effort between the United States, Denmark, and Greenland.

Our first task upon arriving was to help unload, assembly line style, all of the food from the plane to the main building, the Big House. There was a ginormous amount of food that needed unloaded, so this took about thirty minutes…thirty minutes too long for the extreme temperatures! After a very serious safety briefing for all the new arrivals, I was free to go about my business for the next four days! That is, after lunch of course! The food at Summit is definitely something to write home about! Upon arrival, there was several plates of freshly baked cookies waiting for us. It was great to taste some good American sweets once again! The cooks that are on-site do an incredible job of making tasty food and raising the moral of all the scientists. Every time I sat down for a meal, including the very first which was lobster bisque, I knew it was going to be delicious. The shear quality and amount of food at such a remote location was astonishing to me.

Most of the new arrivals took it easy the first day, as either a symptom or just a precaution for altitude sickness. Summit is located at the pinnacle of the Greenland Ice Sheet, at an elevation of 10,600 feet. Since it is also located so far northward (72 degrees), the actual altitude you body feels approaches 12,000 feet at times. For the duration of my stay, my room was Solar Tent #4. It was one of 20 tents set-up in what is called “Tent City.” These tents, during the daytime, actually get quite warm; I figure somewhere around 40 degrees. Unfortunately, as nice as that sounds, you do not spend anytime during the day in your tent. At “night,” when the sun is at a much smaller elevation angle, the tents are marginally warmer than the ambient outdoor temperature. Fortunately for me, I was equipped with a sleeping bag rated to -60 degrees, and the coldest night was only twenty below zero.

A view from my tent in Tent City. The building in the back on stilts is

the Big House, where meals are served and people hang out.

—

I spent a majority of my time trying to learn the tasks that I will be charged with doing in February when I return. Aronne was training his replacement Nate, both students from the University of Wisconsin, who are working on the same (yet different) project as me, on how to maintain the slew of powerful atmospheric remote sensing instruments we have in such a harsh environment. Some typical daily tasks include checking to see that all data look good and that no instruments are covered in ice. We are also in charge of launching twice-a-day radiosondes, which give insight into the temperature and moisture of the atmosphere above. These devices are affixed to helium balloons and travel upwards taking numerous measurements above the surface and are launched all over the world at precisely the same time. This allows atmospheric scientists to get snapshot of the entire world’s atmosphere two times per day!

Other than learning the ropes, my boss also gave me a few small tasks to repair some instruments while I was on site. My first task was to replace a part on a lidar. This was a fairly trivial task, but things became significantly more complicated when we started having software issues after the repair. Luckily, with the combined efforts of two other scientists and myself, we were able to get the lidar up and running!

The crowd at Summit was a mix of young graduate students and more seasoned scientists, mechanics, cooks, and medics. This made for a very unique atmosphere. After a hard day’s work, evening activities included playing cards, watching movies, throwing Frisbee, sipping hot chocolate together, and my personal favorite, playing bocce! Sure it was below zero and pretty damn windy, but how many people can say they played bocce on the Greenland Ice Sheet? This game, which is already fun to play at home in a lawn setting, was orders of magnitude more awesome to play in an extremely unpredictable snow/ice setting in full extreme cold weather gear!

A late night game of Ice Sheet bocce. We were so official and actually used a measuring tape to determine the winner of each round!

Most if not all the structures at Summit are built to counter snow drifting, which is a major problem here. Snow at the surface is often powdery and gets picked up by the wind easily. A majority of the Ice Sheet is a flat, featureless expanse of ice. This offers very little friction to slow down the wind, meaning winds here are fast, commonly approaching hurricane force in the winter (making for unimaginable wind chills colder than -100 degrees Fahrenheit). Many of the buildings are up on stilts and can be jacked-up as necessary. The ones that are not on stilts do get buried, and must be dug out, lifted, and re-positioned annually.

The only source of fresh water in this remote of a location is the snow. Large machines scoop up shovels of snow from designated locations and place it into hatch where it is melted by the excess heat from the giant diesel generator that powers the camp. This process is not very efficient, therefore causing showers and laundry to be severely limited on-site. Black flags mark the 12-foot deep pits where the snow is excavated to prevent anyone from falling in. Red flags, like the one shown here, mark the path from one building to another. In some cases during storms, visibility becomes so limited (usually from blowing snow, but also from falling snow) that these flags are needed to get around and lessen the chances that someone could get turned around and get lost on the ice.

We received a very welcomed atmospheric treat from Mother Nature one day I was at Summit….SNOW! My colleague indicated that this event was the most snow he had seen since he arrived in early April. Though it may be hard to believe, it rarely snows here. Like many places in the Arctic, the air is just so cold that the atmosphere can not efficiently precipitate. The real reason Summit appears to be so snowy is because any snow that falls basically never melts! This elevation and latitude, combined with the high solar reflectivity of snow (~65% of suns energy that strikes the ice sheet is reflected, compared to a forest where only 5-10% is reflected) prevents temperatures from getting above freezing. This is the reason why the Ice Sheet still even exists today and is actually fairly stable (i.e. won’t just melt in a few decades).

On my last night at Summit, I was able to witness a cool optical phenomenon known as a sundog. These rainbow colored halos form around a low-angle sun in the sky when very fine ice crystals are present in the air through a deep layer. On this occasion, a strong wind was kicking up snow from the surface. These phenomenon are actually fairly common atop the Ice Sheet, but are also visible around the world through a varying number of circumstances.

LEAVING THE ICE

The C-130 landing at Summit on the snow-packed runway, or skiway as they call it. Notice the skis the plane has instead of wheels.

My final morning at Summit before the plane arrived to pick us up was a balmy 28 degrees. This abnormally warm temperature made the snow-packed runway a little slushy. The plane landed, cargo was unloaded, and without further adieu, we boarded for take-off. The plane sped up for take-off, like any other plane would. After about ninety seconds at this high speed the engines shut off and the plane rapidly decelerated, stopping just shy of the runway’s edge. An airman from the cockpit signaled for the guys in the back to move baggage to the rear of the plane. Actually taking off on a slushy snow surface is no easy task…especially with a few palates of cargo and twenty passengers. The plane could just not get enough speed with the increased runway friction. After moving the baggage, they gave it another go….fail. The airmen then proceed to move passengers to the back of the plane to sit on the floor. We were all strapped in like cargo. It was at this time that the guard guys cautioned us not to take any pictures. One girl’s camera was actually temporarily confiscated. This procedure was clearly against some sort of protocol and they did not want any record of it. On what seemed like our fourth or fifth take-off attempt, you could feel the nose of the plane finally get good elevation..and even the whole plane off the ground. After violently slamming back onto the snow surface several times, giving everyone that was strapped to the floor a hardy jolt, the C-130 made it airborne! This somewhat frightening event was over! A round-of-applause and cheers emanated from the rear of the plane, from passengers and airmen alike. It was all smiles for the duration of the two-hour return flight to Kangerlussuaq. I took several photos out of a window in the plane..

Near the edge of the Ice Sheet, spectacularly colored blue melt ponds and streams can be seen from the window of the C-130

We arrived in Kanger to mostly sunny skies and temperatures in the mid 70’s! This was almost warmer than in Colorado on this day! Unfortunately, our arrival also just succeeded the spring hatching of the Arctic mosquitoes. They were everywhere! I stopped in at the Pizzeria again, as there are only like four restaurants in the whole town. The Turkish man is apparently allergic to mosquitoes, or so he claimed. The entire room reeked of bug spray. While we were waiting for our food to be cooked, he must have sprayed himself or the room ten times. I will give it to him, I did not see one mosquito inside his establishment. There were dozens flying into the screens of the open windows. On our prior trip a week earlier, we had eaten outside behind the building on some well made Danish picnic tables. This was not even an option this time! We hung out inside and ate standing-up watching a news broadcast in Danish with Greenlandic subtitles. Yeah, it was that bad outside!

On my last night in Greenland, even with the rampaging mosquitoes outside, I decided to hike to a spot that is frequented by a herd of local musk ox. It is up and over a ridge on the opposing side of the fjord from the town. I set out around 8PM. This hike was significantly easier as I was just following a sand and gravel road that was not all that steep. I made it to the top of the ridge but could not immediately spot any musk ox. There were foot prints from these massive animals everywhere, and even some balls of their thick fur lying around. The mosquitoes got noticeably worse the farther I trekked away from town. Finally I could no longer take them and speed-walked back home without seeing any musk ox. This was disappointing, but I still was glad to experience spring in Greenland one last time before departure.

One of my last glimpses of the Greenland tundra…just beginning to turn green. Mother nature reclaims this area each September and returns it to a barren, icy land.

BACK TO AMERICA!

The following morning I awoke at around 4AM and got breakfast at a buffet-style place in the airport. The food here is nothing too special, just your typical European breakfast: eggs, bacon, bread, juice, yogurt, coffee, soft-boiled eggs, and sausage. 3 flights, 2 bus trips, a taxi ride, and 22 hours from the time I woke up, I arrived home to Boulder. To top the day off the airline lost my luggage..yes the giant blue duffel bag. Unfortunately, I had been forced to quickly repack my bags at the airport in NY earlier, so many of the items that were in the lost bag I needed. What an exhausting trip! As soon as I got home to my room I threw all my bags down and passed out.

Even with the extreme cold, mosquitoes, lack of civilization, and barren landscape, I still would recommend a trip to Greenland to anyone. It it almost unimaginable that there are places on Earth like this, so far at the complete other end of the spectrum from most places in America. Seeing animals and plants thriving in an area where winter lasts nine months out of the year is remarkable. This trip has given me great insight into what I will be dealing with when I make my return, extended multi-month trip in February when it will be ridiculously colder and near 24-hours of darkness.

Click to collapse this post

.

In Part II of Life Below Zero, I will cover the physical training and medical clearance needed to travel to Greenland, my second and much colder trip up north in the middle of polar winter, and a bit of the science behind my research. Thanks for reading!

Read “Life Below Zero: Part II” HERE

.

You must be logged in to post a comment.