In this third, and possibly final portion of the Life Below Zero series, I cover the perilous flight from Iceland to Greenland, some of the nuances of life on the Ice Sheet, and my unexpected departure from Greenland due to medical concerns.

Be sure to read Part I and Part II of the series if you didn’t already. Enjoy!

JANUARY 2012

Landing at Fifty Below

In this post, I review the exciting flight from Iceland into the ice-cold heart of Greenland.

Click to expand this post

The Eastern coast of Greenland. Sea ice to the left, a snowy beach in the middle, and inland mountains to the right!

The flight from Iceland to Summit was a long one! We completed it in two three-hour stints, stopping once at a small Danish airbase along the eastern coast of Greenland to refuel. The cabin of the Twin Otter is not pressurized, so it flies quite low to the ground.

Eastern Greenland is very mountainous. The pointy peaks of this mountain range are the largest in the country.

The views out the small porthole windows of snow capped mountains, endless ice, frozen fjords, sea ice, and glaciers were visible in great detail due to this low flight altitude. The terrain of eastern Greenland is quite remarkable…significantly more mountainous then western Greenland which I have flown over before. The jagged peaks towered out from the ice sheet several thousand feet into the sky. This outlandish terrain seemingly stretched for hundreds of miles, something I had not anticipated. Once past the mountains, it was nothing but flat ice sheet the entire way to Summit. There were beautiful clear skies over the ice for several hundred miles, but just before reaching Summit the ground disappeared behind very thick and shallow fog. This fog was the reason our flight was almost postponed. However, based on some meteorological observations taken on site at Summit, an improving forecast for the area, and an optimistic judgment call by the pilots, the flight was not scrapped.

The five crew members on the ground were anxiously awaiting our arrival, having seen no one except their tiny group for the past four months. They had spent the entire morning preparing for our landing. The runway, if you can really call it that, was compacted a bit to get rid of some drifted snow. It is composed of the same snow and ice that makes up the surrounding 500,000 square miles of ice sheet. The only way the runway can be discerned from the sky, fog, and surrounding “normal” snow is by black flags which line its edges. These flags, which are crucial to a successful landing, quickly become white from blowing snow and riming (freezing fog). Ground crew must drive around on snowmobiles and scrape these flags free of snow immediately prior to a plane’s approach. Additionally, preparations must be made to refuel the plane and empty its cargo as soon as possible upon landing. At the extreme temperatures of Summit, the risk of an engine locking up are real and can happen very rapidly if the plane remains on the ground too long. This is because motor motor oil and gasoline solidify at temperatures near -55 degrees!

One last look at our plane as I headed inside for lunch. The ground crew (i.e. other scientists) was already unloading our bags and the plane’s cargo with snowmobiles towing sleds.

I was quite concerned about our landing as we slowly descended into the fog. I knew we were already very close to the ground before we started descending. Every time I felt little spurts of descent in my seat, I just envisioned our plane slamming into the icy surface. Looking out the window, everything was white. There is no way to see the white ground through a white cloud of fog. Just when I was about as worried as possible, thinking to myself “There is no way we didn’t hit the ground yet!”….the plane started to rapidly ascend. The pilots came over the intercom and said that they could not find the landing strip and were looping around to try again. It was at this point I questioned if we were actually going to make the landing or come back another day, but also how close we really were to the ground before the pilot pulled the plane up. On the second attempt, now coming from the other direction, the runway flags became visible to me just before touching down on the ice. Talk about a miracle landing. The landing itself was very smooth and we decelerated quite nicely. I was second to climb down the ladder. My feet hit the snow and I was scurried to the dining area for lunch, inside and out of the fifty-some-below temperatures!

What a trip! It took four days and five separate flights to get to Summit, with a total air time of about 20 hours. That is apparently what it takes to get to this remote of a location. I feel very lucky to have safely landed in such a harsh environment with relatively no problems. I am thankful for all the people that worked hard in getting us here without incident, especially the brave (though handsomely paid) pilots of our Twin Otter!

Click to collapse this post

FEBRUARY 2012

Summing Up Summit

Here I discuss some general aspects of day-to-day life in Greenland, including how we combat the weather, housing, and some potentially life-saving safety precautions that must become habit immediately.

Click to expand this post

I thought I would take this time to give a little more background and general information about Summit Station. Summit is strictly a science-based outpost that focuses on understanding the changing climate of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Projects located here are quite varied, including simple surface-based meteorological observations, pollution, aerosols, snowfall accumulation, snow albedo, energy balance, and my project that looks at clouds,as well as much much more. Summit has been growing in the last 20 years, and has been renamed to reflect this change in size to Summit Station, from the previous Summit Camp!

Summit is located at the very top of the Greenland Ice Sheet, at an actual altitude of 10,700 feet above sea level. However, because the air is very cold and dense here, the pressure is equivalent to an altitude of about 11,700 feet in Colorado, where the air is much warmer. Summit lies more than 400 miles from the nearest point of land, surrounded by nothing but ice. Surprisingly, even in this secluded of a location, many birds and a few stray Arctic foxes have turned up around the station. Last March, Summit set the record for the lowest surface temperature ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere, falling to a bone-chilling -88 degrees Fahrenheit, not even accounting for the wind. Only a few places in Russia and Antarctica have been colder. Temperatures can vary widely all year round. Since I have arrived, temperatures have ranged from -8 to -55 degrees. I know that during the next few months I will be seeing temperatures in the -70 to -80 degree range!

Aurora from the other night. No one would let me get my camera because they said this one was not worth it! I look forward to when there is a real show!

Summit is situated at approximately 73 degrees north latitude, well within the Arctic Circle. There are two important consequences that arise from its location. First, Summit is located directly within the major Geo-magnetic belt of the earth, meaning it has one of the best chances of seeing the beautiful green, red, and purple hues of the Northern Lights (aurora borealis) on most nights. Unfortunately, however, most of the time Mother Nature’s displays are hidden by clouds that so often fill the skies here. Another consequence of Summit’s northward location is widely-varying daylight cycles. Currently there is approximately three hours when the sun is above the horizon. However, it is fairly bright out between 7am and 6pm. The sun moves incredibly slow here. The reds and oranges of sunrises and sunsets last for several hours, unlike at lower latitudes where they may last but ten minutes. Also interestingly, a shift from 24 hours of darkness on Feb 1st to 24 hours of daylight by May 1st occurs, a gain of 24 hours of daylight in about 90 days. That is an increase of about 20 minutes of light per day. This compares to typical gains of around a minute or two of daylight per day in the United States.

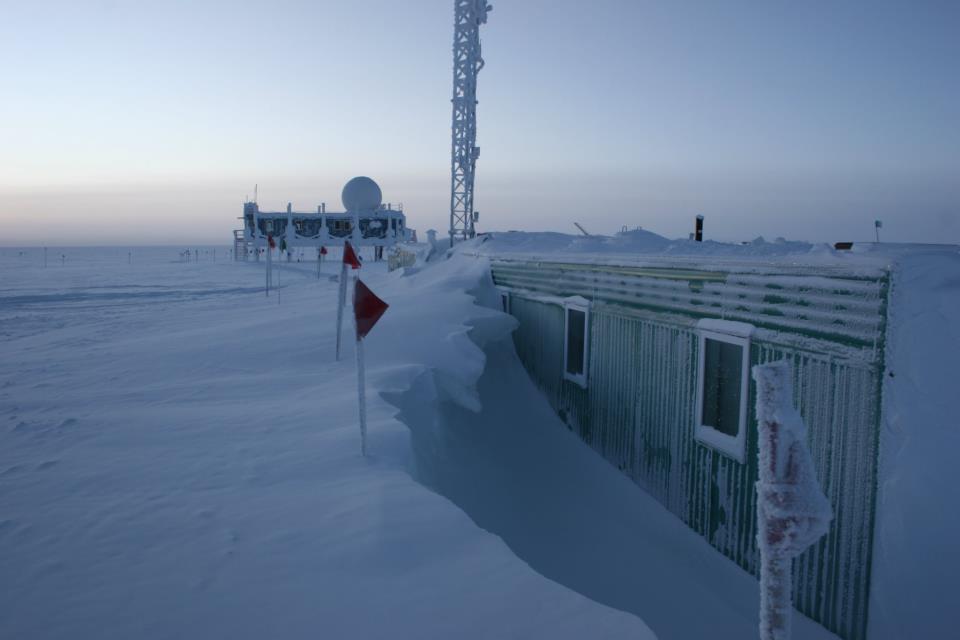

The Greenhouse. My bedroom is the window in the middle. A few more wind storms and my view will be gone! BTW my window faces perfectly to the part of the sky where auroras form nightly! Pretty awesome!

An ice sheet is exactly that, a sheet of ice! When walking around, you hear the familiar sound of crunching snow beneath your feet that you would hear anywhere in the wintertime, but you also her a sort of icy creaking sound as well, a definitive indication of what lies below. The snow just becomes more and more compact as you go further beneath the surface, to the point where it eventually can be considered ice. The Greenland Ice Sheet itself formed around 100,000 years ago when Earth was in a much colder phase. Summit is located atop 2.3 miles of ice, the thickest portion of ice in the Northern Hemisphere. The weight of the entire ice sheet, which covers more than 85% of Greenland, has depressed the Earth’s crust several hundred feet below sea level. In other words, if the ice sheet were to melt completely, Greenland’s interior would mostly be submerged beneath the ocean.

How does an ice sheet form you ask? It takes several thousand years of precipitation (snow) exceeding the rate of melting. The Greenland ice sheet has net growth at places in the interior like Summit, where no melting occurs and it snows year round, but has net melting near the coasts where temperatures warm in the spring and summer. Here at Summit, the surface rises approximately 3 feet each year from accumulating snowfall. This means that after just three years, a one story building would be buried! To combat the rising snow level here, some practices are used. One involves attaching buildings to poles which allow the whole structure to be jacked up each summer. Buildings that are not able to be jacked up (like the Greenhouse pictured above) do get buried and must be dug out each year and re-positioned atop the ice again.

The snow at summit is extremely dry because it is always falling at temperatures well below zero. It is nothing like the wet snow the falls a majority of the time in United States. Think of the most fluffy snow you have ever felt, and imagine snow that is ten times more fluffy. That describes the snow here. Because of this particular property of the snow, it gets picked up by the wind very easily. Even a 10mph wind can cause ground level white-outs here. Winds greater than 25mph lower visibility to less than 50 feet in most cases, increasing the danger when walking between buildings around the station.

Shallow fog layers like this one are often present and reduce visibility as well, not nearly as bad as blowing snow, however.

On that note, there are restricted operating levels for the crew here based on visibility, but also on wind chill temperature. When the wind chill is above -90 degrees, and visibility is greater than 200 feet, it is Level 3. At this level, travel around and off-station is not restricted at all. Yep, if it is warmer than -90 degrees, basically no rules! On-station is considered an area hard to describe, but it is roughly anywhere within a half-mile radius of the main building. Off-station is anywhere outside this circle. Level 2 is when the wind chill is above -100 degrees but below -90 degrees or the visibility is greater than 50 feet but less than 200 feet. This level requires any travel around station to be done with a partner. All off station travel is prohibited. Level 1 is the worst and occurs when either the wind chill is less than -100 degrees or the visibility is less than 50 feet. During Level 1, all travel is completely prohibited. You must stay in whatever building you are in, or get to the nearest building. Each building has a giant “survivor” bag, which contains first aid things, extra clothes, sleeping bags, a tent, rescue beacons, flashlights, and a significant amount of MREs (freeze-dried military rations), just in case you get stuck for days and your building looses power. You need to take these travel restrictions very seriously here. Going outside at Level 1 could be the last decision you ever make. In the week that I have been here, Level 1 has not been reached (it was later while I was there, see video below), and Level 2 has only been realized twice for several hours a pop.

LEVEL 1 VIDEO LINK

Safety here is the number one priority that has to be on your mind 24/7 in every aspect of your daily life. Simple tasks that you take for granted everyday at home must be done with extreme care. In as remote of location as Summit, help could be days away, even in good weather. In bad weather, which is quite common, it could be weeks away. One of the requirements to come here is that each person must have medical training to care for another person if a situation does arise. Additionally, one person must have extensive medical experience, approaching the level of EMT. This is in hopes that if a medical emergency does arise, we will be able to stabilize a person until real medical treatment can be realized. Tasks like walking down stairs, standing on step ladders, and even traversing icy areas must be done with extreme caution. The National Science Foundation, the organization in charge of running Summit, institutes a mind-numbing amount of safety lessons before and as soon as you arrive here. Workers must be educated on safety and sign off on every possible task you could imagine. Some of these tasks include riding a snowmobile, climbing ladders and towers, moving compressed gas tanks, walking on roofs, and even venturing down the icy steps to the sub-surface freezer for food. I literally had to sign off on dishwashing rules before I was allowed to wash dishes (the floor is very slippery in there). They try to prevent and make sure you are aware of any and all potential hazards around the station. Knowing that your odds of timely medical care are very small causes you to keep your own well-being at the forefront during every task, no matter how routine or trivial it may seem.

A sun halo visible to the south around noon local time. This is the suns highest point in the day. This feature is formed via ice crystals in the air.

Summit will continue to grow over the next few years as those interested in the climate change over the Greenland Ice Sheet migrate here. A major project involving a high-altitude telescope, similar to those located in Hawaii, Chile, or in Antarctica, is on the horizon for Summit. Plans to expand the number of permanent structures on-site are already in place. In the summer, when conditions are much more tame, Summit is typically filled with researchers numbering in the dozens and with a full-time staff to meet the scientist’s needs. Who knows, maybe in the next decade the Summit Station will be renamed “Summit City”!

Click to collapse this post

APRIL 2012

An Adventure Cut Short

In this post, I explore my difficult decision to leave Greenland for health reasons.

Click to expand this post

My time in Greenland came crashing to an abrupt end, more than two months early. I came down with a serious medical issue and doctors were not confident the by-phone advisement from a physician in the USA and the meager medications of our remote research camp atop the Greenland Ice Sheet could treat it effectively. It was decided on Monday, Feb 13th that I would have to leave Summit to receive proper medical care, as the last scheduled flight until the end of April was arriving (and departing) that day. However, because of ferocious winds and blowing snow, the plane did not actually land at Summit until Wednesday the 15th. Myself, along with two other site bosses of sorts were just about to board the plane for departure when the wind suddenly picked up and blizzard conditions returned. After an hour or so of debate, it was decided that the plane would not be taking off that day and the pilots would try again in the morning, hoping for better weather. The only problem with this plan is that the plane would have to be stored outside overnight and its engines started again in the morning (which can be a hardcore challenge at 70 below zero). This however was the only option. This is a clear example of the inherent danger that Summit’s remoteness presents. If I truly had an urgent, life-or-death issue, help was four days away because of the unpredictable weather conditions of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Luckily, my issue did not require immediate care or escalate to that point.

By the time I left this trip, we were just beginning to have sunrises and sunsets. Because of the high latitude, each one would last for several hours!

The following morning, on the 16th, conditions improved significantly and the sky was actually clear, which you would assume to be good news. Unfortunately, this clear sky allowed the temperature to plummet to near 70 below zero overnight. The pilots and on-site mechanic were significantly concerned the plane would not start. I forget the name of the machine that was used, but it basically was a giant heater that bombarded each engine, one at a time, with hot air. After warming up enough, the engines started!

Machine being used to warm up the left engine of the twin otter. Tubes being used to funnel hot air directly onto the engine

It was at this point I finally came to grips with the fact that my time in Greenland was actually coming to a close. It was all surreal until the instant both the engines started on this very cold February morning. At this moment of sadness, I felt as though I could shed a few tears, which I learned from this instance is impossible at negative 70 degrees Fahrenheit…

As upsetting as it was to be leaving, to be heading back to the States with a feeling of disappointment, to be letting the other folks in my science project down, to be missing out on building the close-knit friendships you gain by living in seclusion with five other people for several months, to be ending an experience most people only dream of, a tiny part of me was excited to get back home to Colorado and to make the best of this unfortunate situation.

The flight back home was just as brutal as the one to get to Greenland. There was definitely lots of interesting, crazy, unforgettable tales, all of which I am not going to talk about. The only thing that matters is that I made it back safely. By the way, I made a mini-vacation out of my trip home, stopping in Pennsylvania along the way to take some time off. Trust me when I say I needed it. What an incredible feeling it is to see friends and family after being through all I had in the previous several weeks!

Every part of that month, from Boulder, to Iceland, to Summit, back to Iceland, to PA, and finally home to Colorado was an adventure. There was without doubt incredible experiences, some regrets, tedious work, great fun, hard times, good people, scary moments, and of course, delicious food…all of which are memories that will last a lifetime! And what is life without adventure?…not much at all. I leave you with a quote from the movie/book Into the Wild:

“The very basic core of a man’s living spirit is his passion for adventure. The joy of life comes from our encounters with new experiences, and hence there is no greater joy than to have an endlessly changing horizon, for each day to have a new and different sun.”

Click to collapse this post

The “Life Below Zero” series did not cover my final two trips to Greenland in 2013 and 2014. Let me know if you have an interest in these, and I may post parts IV and V someday!

Thanks for reading and I hope you can make it to Greenland someday!

You must be logged in to post a comment.